Andrew McKee, buried at Kilcashel, was born in 1695. Deb found a Baptism record from Minnigaff Parish, Kirkcudbright County for an Andrew McKie, born 1695! Was this our Andrew? We think probably yes, but in any case, it is good to learn Minnigaff history! For the beginning of this story, click back to Exploring McKee Roots in Galloway.

Minnigaff Parish is in the County (shire) of Kirkcudbrightshire. Barry found an interesting County website at: http://www.kirkcudbright.co/index.asp

In this county site there was information from all the Parishes, including a Parish history written by James G. Kinna in 1904- History of the Parish of Minnigaff, now available as an e-book from Google.

This book is particularly interesting to all M’Kie/ McKie /McKee families as Minnigaff is the home parish of this clan, so I uploaded it here as a PDF file – Kinna 1904 History of the Parish of Minnigaff. The quality of this PDF file is low (no word searches, for example) so in February I converted it to HTML, and kept the printed page numbers for reference. For easy access, I divided the book into 20 sections with an index at the beginning.

Early in the book, (index 3) Kinna tells the story of Bruce meeting the widow at Craigenallie with her three sons M’Kie, Murdoch, and M’Lurg along with Douglas and his men. Is this remarkable history true? In this telling, Kinna implies yes , and as a (likely) descendant of M’Kie, I hope yes!

In the middle of the book, (index 5,6) Kinna describes: one of the most stirring epochs in Scottish history — the struggles of the covenanters for religious liberty. — in 1640, Lord Galloway, Sir Patrick M‘Kie and the Laird of Muchmore represented Minnigaff on the War Committee of the Stewartry. In the battle of Newburn the troops commanded by Sir Patrick M’Kie were particularly distinguished for their bravery- – although his only son was lost.

Late in the book, (index 16) Kinna describes a memorial from Sir Patrick McKee in memory of his relatives the M‘Dowall and Gordon families.

If you do a word search for M’Kie you get 16 hits in the text below – but not all browsers allow ‘ – if not use Kie. Searching for Larg yields 37 hits of which 18 are for Larg, and the remainder for larger.

- 1. CELTIC HISTORY – Cairns, Crannogs and Moats

- 2. ENGLISH PRESENCE – Wallace at Wigtown

- 3. ROBERT the BRUCE at Craigencallie and more

- 4. Miscellaneous

- 5. REFORMATION and COVENANTERS

- 6. WAR with ENGLISH – M’Kies Prominent

- 7. WM. of ORANGE

- 8. BILLY MARSHALL and the LEVELLERS

- 9. HERON of BARGALLY

- 10. MINNIGAFF TAXPAYERS, 1642

- 11. TOWER at LARG – once home of the gallant Sir Patrick M‘Kie

- 12. GARLIES Castle

- 13. KIRROUGHTREE + Misc

- 14. VOTING List – 1831

- 15. CHURCH History

- 16. M’Kie Memorial

- 17. Church History

- 18. Ministers in Parish

- 19. Witchcraft

- 20. Church and Court Records

HISTORY of the PARISH OF MINNIGAFF

by

JAMES G. KINNA

DUMFRIES, J Maxwell & Son, Printers and Lithographers

p 1

HISTORY of the PARISH OF MINNIGAFF.

FAR back in the mists of antiquity we find Galloway inhabited by two tribes of Celtic aborigines, the Selgovae and the Novantes. Within the dominions of the latter the parish of Minnigaff is situated. The only remains of these ancient inhabitants now existing are the cairns, crannogs, and moats, dotted over the country. It is wonderful how much of the unwritten history of the past we can learn from the careful examination of those relics which are occasionally discovered on the surface, or are unearthed from the former haunts of the aborigines. Without descending into particulars too minutely, suffice it to say that there can be traced successively the different periods of the stone, bronze, and iron ages. It must not be supposed that all the remains which have been found are indicative of perpetual inter-tribal warfare. In several instances – if not exactly in Minnigaff parish, certainly near it — articles of ornament have been discovered. And as a proof of the high state of civilisation attained by our remote ancestors, it may be mentioned that. there was lately found in a crannog the well-preserved remains of a bone comb. There are few parishes in which more pre-historic remains are to be found than in Minnigaff. But, unfortunately, large numbers of cairns have been utilised for dyke building, to the great diminution of objects of antiquarian interest.

Frequently during the removal of cairns many curious “finds” have been made, but being of no pecuniary value they were not preserved. Happily such is not now the case, as objects of antiquarian interest are now eagerly bought up at fancy prices, so much so that recently attempts have been made to palm off spurious articles on the unwary. “Feyther, wull that broon jug ye made dae for the minister, noo, whun he comes roon lookin’ for auld things?” “No; it’s no hard eneuch. Gie it anither week in the sun. But the auld ax ’ll be roosted eneuch; try him wi’t, he’ll likely tak’ it.” This much for the profitable manufacture of relics. So far as I can learn the most frequent finds have been urns of different sizes and shapes. This leads me to suspect that all the cairns and tumuli in our parish belong to the class commonly called sepulchral cairns.

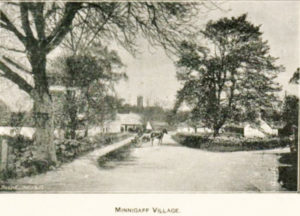

Photo of Minnigaff Village

It is difficult to account for such a large number of funeral remains in so limited an area, but I have conjectured this must have been the locality in which the great battle between the Romans and the Picts allied against the Scots raged most fiercely. When it is remembered that within the policies of Kirroughtree these cairns can be counted by scores, it will be admitted that this locality has as much claim to be recognised as the theatre of this ancient battle as any other place in Galloway.

This sanguinary encounter is thus referred to in Buchanan’s History: — “During the reign of King Eugenius, the Roman Lieutenant Maximius, expecting to possess the whole island, if he could only destroy the two northern nations, commenced his operations by pretending friendship to the Picts. As their circumstances were the more depressed, and they were therefore the more ready to listen to terms of pacification, he buoyed them up by magnificent promises if they would prove sincere in their attachment to the Romans, and besides innumerable other advantages he offered to concede to them the whole territory of the Scots. The Picts, blinded with rage and eager for vengeance, allured by his promises and regardless of the future, willingly listened to the General’s proposals, and in conjunction with the Romans ravaged the possessions of the Scots. The first engagement took place on the banks of the Cree, a river in Galloway. where the Scots, being inferior in strength, were overcome by numbers. While they fled on all sides, the Romans, certain of victory, pursued without regularity, but in the midst of the pursuit the troops of Argyle and other remote districts, who had not yet joined the army, arriving in good order fell upon the dispersed Romans and occasioned a great slaughter. Eugenius, profiting by this circumstance, rallied as many as he could of the fugitives and held a council of war on the present state of his affairs, when finding that with the forces he possessed it would be hopeless to renew the engagement he retreated into Carrick.”

The slaughter was so excessive on both sides — if we may believe the averments of some historians – that the Cree became discoloured with the blood of the wounded, and almost choked up with the bodies of the slain. It is strange to reflect that the Cairns with which we are so familiar have existed for more than fifteen hundred years. What mighty changes have taken place in that time? Cities once fair to look upon have risen, flourished, and are now passed away. Even Rome, whose imperial eagles then fluttered over the known world, is now scarcely the shadow of its former self.

Rome! Rome! thou art no more,

As thou hast been,

On thy seven hills of yore,

Thou sat as a Queen.

Thou had'st thy triumphs then,

Purpling the street,

Princes and scepter’d men,

Bow‘d at thy feet.

Still these old grey cairns remain telling the story of their origin to those who care to know. It seems almost sacrilege to meddle with any of them, but in this age of research nothing is too venerable to escape investigation. Those which have been disturbed, besides yielding evidence of having been places of burial, sometimes contained curious relics. ln the year 1754 some of the cairns in Kirroughtree Park were opened, and in one of them were found three pieces of armour. One of these was formed very much like a hatchet, but subjoined to the back of it there was an implement resembling a pavior’s hammer. The second resembled a halbert. The third was like a spade, but much smaller in size. Each of these articles had a proper aperture for the handle. When they were first discovered they were so much covered with rust, with which they were corroded, that it was impossible to distinguish of what metal they were made, but they were at last found to be of brass. They lay for many years in a farm-house in the parish, but it is not now known what became of them. We have several times assisted at the opening of cairns, but have never been so fortunate as to make any important find. The last cairn yielded, after a two days’ attack, the head of an old tobacco pipe, similar to those in use a hundred years ago, showing that the cairn had been rifled at some former time. Our other finds consisted of pieces of urns, of different patterns, and fragments of “food vessels,” which confirmed our opinion that most, if not all, the cairns in the parish belong to the sepulchral order

The following account of the opening of a cairn in Kirroughtree Park is taken from the appendix to Symsons’s Large Description of Galloway, where it is reprinted from a MS. account of the parish written during the 17th century: — “ Mr Heron one day making pitts for a plantation of firs in that plain was persuaded by a friend standing by him to open a large mount of earth standing in the middle of the ground, and to take the old earth to put into the pitts to encourage his trees to take root, and upon opening of it found it to be a Roman urn. The top of the mount was all covered over with a strong clay, half yard deep, under which there was half a yard deep of gray ashes, and under that there was an inch thick of scruff-like mug metal, bran coloured, which took a stroak of the pick-axe to break it, under which the workmen found a double wall, built circular ways, about a yard deep, full of red ashes like those of a great furnace. When these were taken out at the bottom there was a large flag-stone six feet long and three broad covering a pit of a yard deep, and when they raised up the stone they observed the bones of a large man lying entire, but when they struck upon the stone to break it they fell down in ashes. There was nothing more found in it. There is above a dozen of great heaps of stones detached over the plain in which were found several urns, but none so memorable as this.”

It is supposed that this cairn was situated half a mile east of Kirroughtree house. Several of the Minnigaff cairns have names descriptive of colour – or some other obvious characteristic. Such is the Boss Cairn, so called from a singular cavity, which many years ago was laid open. The Grey Cairn and the White Cairn acquiring their name from their general appearance. But such names as Drumawhinnie and Rory Gill’s Cairn are not so easily explained. It has been suggested that the name Rory Gill is a corruption of Ruairi, meaning the tawny chief, and Gall a stranger, so that according to this translation Rory Gill was a dark chief and a stranger, and that at his death this cairn was raised to perpetuate his memory.

It cannot fail to have struck most people that two adjectives, “Black” and “White,” occur very frequently in connection with names of places in this parish. I shall attempt in as brief a manner as possible to show how the “Blacks” and “Whites ” come to be so-applied.

p 10

As the places these adjectives distinguish are not blacker nor whiter than the adjacent country, it is quite clear that these distinctions could not have arisen from such topographical differences. It is true there are cases where the terms black and while have been applied because they denoted some apparent and striking feature in the landscape; but in most cases no such explanation is now satisfactory. But what about the settlers in the so-called black and white districts? It is now generally

believed amongst those who have made this subject their special study that those localities which yet retain the distinguishing adjectives black and white were formerly inhabited by tribes of different colours. And since the waters of the Black Sea are not black, nor are the waters of the Red Sea red, it is beyond doubt that these seas took their names from the presence of former inhabitants of their shores. For the same reason the blacks and whites of Minnigaff are indebted to former inhabitants for their origin. It is a fact that Galloway was the last portion of Scotland held by the Picts in a semi-independent state, and consequently if any part of the Pictish people might be expected to retain their peculiar languages and characteristics it would be the Picts of Galloway. In pointing out a few of those places whose names still bear the memory of their black inhabitants, it will be noticed that these black names occur near the locality of the Pict’s Dyke or Deil’s Dyke, which runs through a part of Minnigaff parish. From the foregoing facts I think it is only reasonable to suppose that the blacks and whites of the parish are only the names derived from former inhabitants, and have no reference to the topography of the several districts so distinguished.

Incidentally I may mention that there are the remains of what has been a very primitive village near to Rory Gill’s Cairn. The bee-hive houses of which the village consisted may be either assigned to the pre-historic era or to the time of Rory Gill, both historic and pre-historic remains having been dug out of the ruins of such dwellings. Certain it is that the remains of such erections can be clearly seen in the locality of Rory’s Cairn.

There is also a bee-hive town close to the moat of Torquhinnock, but in this instance the houses have communicated with each other, though having had several entrances to the agglomeration of huts. Perhaps each group of houses would compose the dwellings of four or five families, who might be spoken of as dwelling in one mound, rather than under one roof.

The walls of these primitive houses are built of rough, undressed stones, and the dome shape or bee-hive form is given by making the successive courses of stone overlap each other till nothing is left but a small hole at the top, through which the smoke escaped. “The principle of the arch is ignored,” says Dr Arthur Mitchell in “Past in the Present,” “and the mode of construction is that of the oldest known masonry.” Such primitive places of abode are yet found inhabited in Scotland, hut there are none in the parish of Minnigaff from which smoke now ascends.

But to return to Rory Gill. He appears to have been the Robin Hood of Galloway, and his end is thus commemorated in a poem by Joseph Train, the antiquarian correspondent of Sir Walter Scott. Rory appears to have been caught red handed in one of his predatory excursions, and summarily dealt with.

No justice ayre was called to ordain,

If his life should be spared or straightway ta'en,

On earth, to make up his peace with heaven,

An hour was asked but it was not given;

And long ere his men could rise on the hill,

Still hanged on a wuddy was Rory Gill.

Thus fell in his prime the bravest wight

That ere gear hunting went at night;

Lamented he was though far and near

The country long he had kept in fear.

And down at night from the blasted tree,

By his merrie men carried away was he,

And where bridle paths on the mountain meet,

They laid him out without a winding sheet,

Save the heathery turf that wrapt his breast,

And left him with tears to his long. long rest.

And oft the wanderer steps to see

The big cairn raised to his memory,

And many bosoms with awe yet thrill

To hear of the deeds of Rory Gill.

Altogether in the parish of Minnigaff there are over one hundred cairns of various sizes, and probably a great many more have been utilised in dyke building

Moats. – There are three moats still existing – one at the Church, another at Little Park, and a third in Bardrochwood Moor. Various have been the conjectures as to the purposes for which these mounds were originally constructed. The general opinion is that they were places of justice before the institution of regular courts. It is stated in the MS account of the parish to which we have previously referred, that “ the moat at the Church was at first contrived for sacrificing to Jupiter and the heathen gods, but when Christianity obtained it was used as a mercat place for the inhabitants to meet and do business till such times as villages were erected, and places of entertainment prepared, and ale-houses for converse, entertainment, and interviews.” This explanation of the origin of moats is quite feasible when the moat occurs in the vicinity of a village, but it does not hold good when applied to such a place as Bardrochwood Moor, where it is more than probable a “mercat” never was held.

Sometimes moats were used as places of execution before the abolition of hereditary jurisdiction. In fact, a moat was considered a necessary appendage to a gentleman’s house in former times. and to possess the right of pit and gallows was a patent of aristocracy.

In those barbarous days feudal superiors who possessed this right— or wrong–could hang any offending vassal, or drown any female thief within the hounds of his estate. It is believed by some, and doubted by others, that the term Gallow Hill had reference to this summary mode of procedure. This name also occurs in the topography of Minnigaff. On the farm of Kirkland is a Gallows Knowe, and tradition affirms that it was on this spot that M K’Clorg, the smith of Minnigaff, was hanged by Claverhouse in Covenanting times. Claverhouse, in a letter addressed to the Duke of Queensberry. says:— “That great villain, M K’Clorg, the smith of Mennegaff, that made all the clekys and after whom the forces have trotted so often, it cost me both paines and money to know how to find him. I am resolved to have him, for it is necessary I mak’ som’ example of severity, lest rebellion be thocht cheap here.” An old gnarled thorn till within recent years marked the site of the gallows. Amongst the great blessings of enlightened times may be included the abolition of hereditary jurisdiction, which took place in 1746. It is questionable whether the old method of administering the law was not better than the present cumbersome and expensive machinery. At all events the old system was speedier than the new.

Crannogs. — There are traces of several crannogs in Minnigaff parish. Vestiges of one of these ancient dwellings can still be found at Larg Tower. The level plain has been at one time the bed of a lake, and even yet when newly ploughed the sites of the ancient hearths can easily be identified by their peculiar red color Another peculiarity in the field is the causeway which traverses its whole length from north to south.

In the early history of the human race self-preservation seems to have been an idea as deeply rooted in the mind of man as it is now. This is evident from the care taken by the ancients to select a place of safety for their homes. No historical era can he fixed when these crannogs or lake dwellings were inhabited, – and we can only judge of their age by sequences. That they were the residences of primitive families all antiquarians are agreed, and the attention which is now being turned to this particular branch of archaeology is being rewarded by some very interesting discoveries.

As the arts progressed and men were able to defend themselves on land from the attacks of wild beasts and enemies the crannogs were deserted. To the crannog as a place of safety succeeded the British fort. One of these ancient strengths is to be found at Larg over-looking the former lake dwelling. In course of time, as civilisation advanced, a knowledge of architecture began to dawn on the natives of this land, and we find the fort being evacuated in favour of the primitive stone building, and I have no doubt that in place of the present ruins of Larg Tower at one time there would stand an example of early Celtic architecture.

Thus runs the sequence crannog, fort, castle, the remains of each may yet be seen in close proximity on the farm of Larg. These rude dwellings of the natives continued longer in use in Galloway than in any other district in Scotland. As the surface of the ancient province was formerly much more covered with wood and water than it is now, it offered special facilities for the construction of these “wigwams.”

Galloway, at the time of Agricola’s first attack in the year 78 A.D., was thickly covered with wood, which greatly impeded that General’s march. Subsequent mention of the woods of Galloway is frequently made, and nowhere can the trees of that ancient period be seen to greater advantage than in some of the mosses in the more northern districts of the parish.

Very large oak trees have been laid bare on some of the farms near the mouth of the Cree, but it is generally thought that these giants of the forest found their way to such low-lying ground through washed down by “spates.” The Wood of Cree, which was formerly celebrated for its oak trees, was sold by Lord Galloway, about the year 1798, for 6000 guineas.

Among the natural curiosities of the parish may be mentioned the Rocking Stone, opposite Dalnotery old Toll House.

We do not find a reference to Minnigaff for many centuries after the battle in Kirroughtree Park between the allied Romans and Picts against the Scots. The Gallowegians were continually in a state of turmoil, and if not engaged in inter-tribal warfare were ravaging some other unhappy locality.

It is thought that the Irish Picts introduced into the parish the practise of brewing ale from heather about the year 1000. Fortunately for posterity this is now a lost art, but some of the places where this process of distilling was carried on existed till within recent years. The Picts kilns, as they were called, were about 15 feet long and 8 wide, and their shape resembled that of a pear. There were several of these curious relics of antiquity on the farm of Risk, but like many other mementoes of a bye-gone age they got utilised – in this case in dyke-building.

The fortified promontory of the Mull of Galloway – says a writer in Vol. VI. of the Archaeological and Historical Collections of Ayr and Galloway – is locally believed to have been the last stronghold to which the Picts of Galloway retired before an overwhelming force of Scotic invaders. At last all were slain except two men, father and son, who were offered their lives on condition that they would reveal to their enemies the coveted secret recipe of brewing heather ale, a beverage highly esteemed at the time, and the preparation of which was only known to the Pictish race. “I will reveal the secret to you,” said the father, “on one condition, namely, that ye fling my son over these rocks into the sea. It shall never be known to one of my race that I have betrayed the sacred trust.” The son was accordingly thrown over and drowned, whereupon the old man ran to a pinnacle of the rock overhanging the sea, and exclaiming, “Now I am certain there is none left to betray the secret; let it perish for ever,” and cast himself after his son into the waves.

p 20

In writing the history of any particular parish it is almost impossible to avoid the occurrence of long chronological blanks in the undertaking. Minnigaff is, however, more fortunate in this respect than many other parishes, for frequent reference is made to it in national history, more especially after the appearance of Wallace. After that patriot’s eventful quarrel with the English officers in Lanark, we find him shortly joined by a gentleman of the name of William Kerlie, whose ancestors had once possessed large estates in Wigtownshire. These estates, together with the ancestral Castle of Cruggleton, had been taken by treachery from the Kerlies, and it was one of the first acts of generosity on the part of Wallace to assist his friend in the recovery of his family property.

On his way to Cruggleton, Wallace appears to have encamped near the village of Minnigaff, and a piece of ground on the farm of Borland is still known as Wallace’s Camp. As this flying visit to the parish took place about the year 1297 it proves how tenaciously a name clings to a locality.

When the English governor of Wigtown Castle, John de Hodleston, heard of the approach of the celebrated warrior he fled to his native country. Wallace, upon gaining possession of Wigtown Castle, installed Adam Gordon as keeper. “He then proceeded.” says Nicholson in his History of Galloway, “towards Cruggleton on the same coast, but he found that it would be difficult to take this stronghold unless by stratagem. It stood upon a rock, the base of which at one side was washed by the sea; the other side, or that next the coast, was well fortified, and had a drawbridge for the ingress and egress of the garrison. Having concealed his men from the view of the besieged, Wallace, with his two chosen companions, Kerlie and Steven, entered the water and swam to the bottom of the rock, they then with much exertion clambered up its steep side. The defenders had no suspicion of danger from that quarter, and had placed no sentinels there upon duty. The intrepid heroes entered the castle and made their way to the gate unobserved. Wallace immediately seized the sentinel stationed there in his iron grasp and threw him over the rock. Having opened the gates and lowered the bridge, he blew his horn, when a chosen party of his men, who had been placed in concealment, rushed into the fort and slew every individual who offered any resistance. They found in it some valuable stores.”

Such was the brief siege of Cruggleton Castle. There is now only one arch of a lower hall standing, and it is supported by iron bands. It is probable that Kerlie, from his intimate knowledge of the castle contributed in a great measure towards the success of the undertaking. The fosse to the landward side of the castle can yet be traced; whilst seaward there are still the same beetling cliffs unchanged since the days of Wallace.

It would seem as if Minnigaff had attractions for patriots, for, after the tragic end of Wallace, and during the struggle for Scottish independence, Robert Bruce frequently visited the locality. Of his doings there I shall quote at length from the History of Galloway, being the most graphic, and at the same time the most authentic, record of the King’s doings when in the parish. After encountering many hardships and dangers we find the King, wearied and distressed with grief, keeping an appointment with his brother at the solitary farm-house of Craigencallie. The mistress of it, a generous and high-minded woman, was sitting alone, and upon seeing a stranger enter she enquired his name and business. The King replied that he was a traveller proceeding through the country. “All travellers are welcome,” answered she, “for the sake of one.” “And who is that?” said the King. “It is our lawful sovereign, Robert the Bruce,” answered the woman, “who is lord of this country, and though his foes have now the ascendancy, yet I hope to see him soon the Lord and King over all Scotland.” “Dame, do you love him really so sincerely,” he enquired. “Yes,” she replied, “as God is my witness.” “Then it is Robert the Bruce who now addresses you.” “Ah, sir!” she said in much surprise, “where are your men when you are thus alone.” “I have none near me at this time, therefore I must travel alone.” “This must not be the case; I have three sons, gallant and faithful, they shall become your trusty servants.” They were absent at this time, but upon their arrival she made them promise fidelity to the King, and they afterwards by their valour became his favourites and rose high in his service.

The enlistment of these three sturdy Minnigaff herds in the King’s service give rise to the popular “Legend of Craigencallie.” It is embodied in the appendix to Symon’s Large Description of Galloway, and is there told in the quaint language of two hundred years ago, and it is to this effect:-During the time that the old lady of Craigencallie was preparing a hasty meal for the King her three sons arrived, and then the narrative proceeds to say – “When the King had done eating he ask’t them what weapons they had, and if they could use them. They told him they were used to none but bow and arrow. So as the King went out to see what was become of his followers, all being beat from him but 300 men, who had lodged that night in a neighbouring glen, he ask’t them if they could make use of their bows. M‘Kie, the eldest son, let fly an arrow at two ravens perched upon the pinnacle of a rock above the house, and shot them both through the heads, at which the King smiled, saying, ‘I would not wish he aimed at him.’ Murdoch, the second son, let fly at one upon the wing, and shot him thro’ the body; but M‘Lurg, the third son, had not so good success.”

In the meantime the English, upon the pursuit of King Robert, were encamped in Moss Raploch, a great flow on the other side of the Dee. The King observing them makes the young men understand that his forces were much inferior. Upon which they advised the King to a stratagem: that they would gather all the horses, wild and tame, in the neighbourhood, with all the goats that could be found, and let them be surrounded and kept all in a body by his soldiers in the afternoon of the day, which was accordingly done. The neighing of the horses, with the horns of the goats, made the English, at so great a distance, apprehend them to be a great army so durst not venture out of their camp that night, and by the break of day the King with his small army attacked them with such fury that they fled precipitantly, a great number being killed.

And there is a very big stone in the centre of the flow, which is called the King’s stone to this day, to which he leaned his back till his men gathered up the spoil, and within these thirty years there were broken swords and heads of picks got in the flow as they were digging out peats.

p 26

The three young men followed close to him in all his wars to the English in which he was successful, that at last they were all turned out of the kingdom and marches established ’twixt the two nations, and the soldiers and officers were put in possession of what lands were in English hands according to their merits.

The three brothers. who had stuck close to the King’s interest and followed him through all dangers, being asked by the King what reward they expected, answered very modestly that they never had a prospect of great things, but if His Majesty would bestow upon them the thirty pound land of Hassock and Comloddan they would be very thankful, to which the King cheerfully assented, and they kept it long in their possession.

To anyone acquainted with the locality, the stratagem of the three brothers seems perfectly feasible. The high hill of Cairnbabber, which rises almost perpendicularly from behind the farm-house of Craigencallie, commands a full view of Moss Raploch. A single line of soldiers appearing on the top of this ridge could be spread out at great length, and from the Moss it would be impossible to know the strength in the rear.

There are now no lands in the parish known as the Hassock, but the tradition is that the sons solicited and obtained the bit hassock of land that lies between the burns of Palnure and Penkiln. This hassock of land is an isosceles triangle, the base of which runs. for three miles along the Cree, and the sides formed by the streams of Palnure and Penkiln run five miles into the country.

Emboldened by his success, and having been joined by friends, Bruce determined to search the locality for any of his enemies who might still be lurking in ambush. He accordingly questioned his followers if any of them had any information on this point, as he deemed it not improbable that coming from different directions they might have learned something of the several bands of English scattered up and down. Lord James Douglas answered that he had passed a village where 200 of them were stationed, and reposed in full confidence of perfect security without having placed any sentinel.

Douglas proposed that they should instantly set out and surprise them, and thus they might have an opportunity of retaliating upon their pursuers the injuries which they themselves, had suffered during the day. Orders were immediately given to mount, and the Scots coming unexpectedly on the English rushed into the village and with much facility cut them to pieces.

Although the name of the village is not given where the encounter took place, circumstances point to Minnigaff as being the scene of the conflict. And it is more than probable that numbers took refuge in the Church, for it is a fact that at a depth of two feet under the floor of the old Church there is a deep layer of bones covered with burnt and charred slates of a very rude description. Evidently the Church has at some period been destroyed by fire, but whether this catastrophe was caused through civil commotion or accident, history sayeth not and tradition is silent.

Churches were favourite places of refuge for the defeated in the olden time, but they were not always treated with that reverence due to their sacred associations. During a party battle between the rival houses of Johnstone and Maxwell, a party of the latter took refuge in a Church. The Johnstones collected a large quantity of hay and straw, which they set on fire, and they burned the Church of Lochmaben with all that were in it as a just punishment in their eyes for the destruction of the Castle of Lochwood.

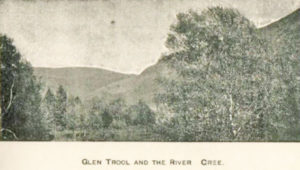

Bruce employed strategy again with success at Loch Trool. The incident is thus graphically described by Captain Denniston, who, besides being well acquainted with the locality, was also an adept in recounting such exploits. He says: – “ Tradition informs us that Bruce retreated to the head of Loch Trool, a wild, romantic, and beautiful lake in the parish of Minnigaff. Bruce, like a wary and experienced general, saw at a single glance the advantages he might reap from his present position, and determined to avail himself of them to the uttermost.

The path that wound up the margin of the lake was so narrow that two men could not walk, much less ride, abreast, while a steep hill, in some places almost perpendicular, arose from the margin of the water, and skirted it for nearly a mile. About the centre of this path the hill pushes forward a precipitous abutment, called still by the inhabitants of this sequestered glen the ‘Steps of Trool.’ The pathway here is about twenty feet perpendicular above the surface of the water, while the hill above is almost the same for a few hundred yards, and very steep for a quarter of a mile higher. It was this spot that Bruce fixed on for the second of his military strategies.

p 30

“ His slender body of troops consisted of a few hardy tried veterans, who stood by him in many a well-contested field – who had braved every vicissitude of season, and suffered every privation, with their undaunted leader. The rest were a body of half-armed and undisciplined peasantry, who had been induced to join him in his hasty marches through the country, and whilst they added to his numerical force were often a drawback on his slender resources, and even retarded the rapidity of the forced marches which his frequent defeats rendered necessary.

“Fully aware that the English would follow, he sent his peasantry up the hill with orders to loosen as many of the detached blocks of granite as they were able to do during the night, and to hurl them down on the enemy at a preconcerted signal, which was to be three blasts on his bugle horn, should they attempt to pass. The reversion of his little band he drew up in a strong position at the head of the lake, and having completed his arrangements he took one or two of his most confidential warriors and ascended a small eminence on the opposite side of the lake to watch the success of his plans. All night his friends laboured with unabated vigour and in solemn silence, so that by the aid of levers and crowbars at the earliest dawn he was delighted with a view of the formidable reception they had prepared for his enemies, and his eye kindled with pleasure at sight of the huge fragments, like the ruins of a wall extending along the face of the hill for almost half-a-mile in length, and his men on the alert and ready for the signal. A glance down the lake showed him the English army in full march up the defile, a body of choice cavalry led the van, a division of heavy armed billmen followed to support them, and the face of the hill was covered with a cloud of archers to protect their flanks. Onward they came in single file, the leading horseman had reached the fatal ‘step,’ when, hark! a prolonged note from the bugle awakens the mountain echoes and awakens the slumbering boar from his leafy bed. Hark!, again it is followed by another blast, louder and shriller than the first. Again it sounds, deep, loud, and portentous, like the first note of the coming tempest as it hurdles through the sky. A moment before this the hill lay smiling in all the soft repose of a summer morning, and in another it seemed to have been rent asunder by the surge of a volcano and its contents tossed into the dell beneath. Down!, down! the dreadful avalanche descends, leaping and bounding and tearing up and breaking down everything that obstructs its fatal progress; but woe to the predestined wretches that were penned up for slaughter in the pathway beneath. In vain were there screams for mercy where no mercy could be shown them. Let us not spin out a tale of horror, nor gloat over the wreck of the human race. The whole of the English vanguard are said to have perished in the defile, and the rest to have become so intimidated that they retired beyond the Cree into the County of Wigtown to await a reinforcement before they resumed offensive operations.”

Various implements of war have been found at the scene of this mishap to the English, together with several buttons of an antique pattern. The nature of the soil in the locality is such that it possesses in a high degree the property of preserving any metal substance which may become embedded in it. The supposition is that the articles which have been dug up from time to time are relics of this ancient fray. A more sanguinary encounter between the English, having the Gallowegians as allies, and Edward Bruce – brother to the King — took place on a plain near Caer-Uchtred (Kirroughtree) about the year 1307.

The Gallowegians, unable to withstand the valour of their antagonists, were routed with great slaughter and put to flight. M‘Dowal, the most formidable enemy of Bruce in Galloway, was slain. The battle took place in Kirroughtree Park, on the same ground as that fought between the Romans and Picts against the Scots one thousand years previously.

This battle between the English Edward and the Scotch Edward was the last time the sound of war has been heard in the parish. Coins of the reign of Edward I. have frequently been found where the battle took place. It is well known that Edward I. of England was most anxious to obtain the supremacy of all Scotland by fair means or foul, and it is conjectured that from the frequency with which coins of his reign are found, he intended to accomplish by bribery and corruption that which he could not otherwise obtain – possession of the kingdom of Scotland.

After the death of Robert the Bruce, his son, Robert II., a minor, succeeded him on the throne, and Randolph, Earl of Moray, assumed the regency. This ruler administered justice with stern impartiality. He held courts in different parts of the country, and sheriffs of a counties were made responsible for property stolen in open fields, because it was their duty to protect it.

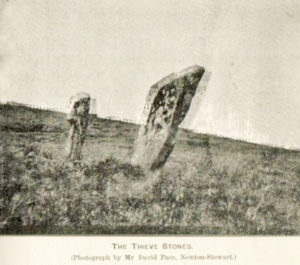

On one occasion when he was dispensing justice in the town of Wigtown, a man stepped forward from the audience and complained that a party of assassins were at that moment lying concealed in a neighbouring forest to murder him on his way home. Randolph immediately sent a number of his attendants to seize the villains and bring them before him. When they made their appearance in the court he thus addressed them -“ Is it you who lie in wait to kill the King’s liege subjects? To the gallows with them instantly.” This powerful gang of thieves who infested the country were, according to tradition, overpowered by superior force, made prisoners, and all executed in the moor of Dranandow in the parish of Minnigaff. Two standing stones, each nearly eight feet high and only a few yards apart, mark the spot where the execution took place. These two upright monoliths are called the “Thieve Stones” to this day.

There were formerly more than two stones standing, but they appear to have fallen down, and are now sunk in the soft moss until they have almost gone out of sight. The locality in which these stones are situated presents some puzzling pre-historic problems, and to all appearance has been the site of one of those bee-hive towns referred to previously in these papers.

As this gang of robbers intended to entrap the Regent on his return from Wigtown to Edinburgh, this circumstance would lead to the conclusion that the direct road from Edinburgh to Wigtown led through Minnigaff, and the assassins were therefore aware that the Regent must pass through their ambush. The leader of the band was Rory Gill, to whom we have previously referred, and whose cairn is yet so prominent an object in the landscape.

What historical events, if any, took place in the parish during the next century or two are not recorded. No doubt the constant state of fear in which the powerful family of the Black Douglas kept the whole of Galloway would be felt in Minnigaff.

After the downfall of these Lords of Galloway, and the annexation to the Crown in 1456, peace seems to have reigned in Galloway for some time.

The fame of the monastery at Whithorn, founded by Fergus, Lord of Galloway, in the middle of the 12th century, had now spread all through Scotland and England, and it was even known on the Continent. To the Shrine of St. Ninian were attracted pilgrims from all parts of the country.

On the 14th December, 1506, the Regent Albany granted a general safe conduct to all persons of England, Ireland, and the Isle of Man to come by land or water into Scotland to the Church of Candida Casa. King James IV. visited Whithorn more frequently than any other sovereign – in fact, once every year, and sometimes twice. He must of necessity have passed through Minnigaff frequently on his way thither, but the name of the “toune” is only once mentioned. The Lord Treasurer’s accounts contain much curious information in connection with these pilgrimages of the King, who usually travelled with a large retinue.

In the year 1507, when the Queen was delivered of her first son – who died next year – she was not expected to live. To propitiate the saints the King undertook a journey on foot to the Shrine of St. Ninian at Whithorn. We are able to follow the King’s route from Edinburgh to Whithorn by the disbursements made by the way, each payment being faithfully noted down.

In March, 1508, we find the King coming from Edinburgh to Whithorn via Penpont, and during the journey the following items of expenditure occur: – “Item, to ane woman that sang to the King, XXVIIIs. Item, for soling of ane pair schune to the King, XVd. ”From Penpont the crossed to Carsphairn, then spelled “Castell Fern,” where one of his outlays is – “Item, for ane sark to the French boy, VS.” On the 16th he breakfasted in Dalry and dined on the way, or as the entry stands, “be the gait,” between Dalry and Minnigaff. Under the same date is the following entry – “Item, that nycht the King soupit at Menegouf, for the belcher there, IXs.” From thence he went to Penyghame on the 17th “and lost Xlls. on schuting with the corsbow with William Douglas – one of his retinue.” On the 18th he was in Wigtown, and the next entry on this journey is – “Item, to ane man that gydid the King fra Wigtown to Quhithorn before day, XIIIs.”

The Queen having recovered from her illness, next year, in the month of July, their Majesties repaired in state to Whithorn to offer up thanks for Her Majesty’s recovery. Their route this year, however, did not necessitate their spending the night in Minnigaff. They were accompanied by a large retinue, Her Majesty travelling in a litter, sometimes called in the Treasurer’s books “the quhenis chariot.” It required 17 horses to carry her luggage, three more for the King’s wardrobe, and one for his “chapel geir.” The journey from Stirling to Whithorn and back occupied thirty-one days.

James IV.’s last visit was in 1512, the year before Flodden. What a stir these grand cavalcades would create during their stay in Minnigaff. One strange fact in connection with these visits of James to Whithorn is that he never made any offerings at the Church of Minnigaff. This might perhaps be explained by his making a present in private, and thus not being a payment of public money, no entry would appear in the public accounts. It would also favour the idea that the vicarage was detached from the Church.

There is a tradition that a religious house once stood a little to the northwest of the present Church; this may have been the vicarage. Be this as it may, Minnigaff Church does not appear to have derived any pecuniary benefit from the passing of Kings and Queens through the “toune.” It would be a matter of some difficulty to find accommodation for a King’s retinue in Minnigaff to-day, but if a King should come we would make an endeavour to make him comfortable during his stay. The next year James, contrary to the superstitious leanings of his nature, and in spite of several mysterious warnings, persisted in waging war on his brother-in-law, Henry VIII. Resolved to invade England at the head of an irresistible force, James summoned all his military vassals, directing them to meet him at the Borough Moor of Edinburgh, attended by all their retainers, between the ages of 16 and 60 years. His summons was obeyed. Out of all the districts in Scotland, his nobles, with their followers clad in armour, hastened to the appointed rendezvous, and on the 9th day of September, 1513, was fought the disastrous Battle of Flodden. The effects of this defeat were keenly felt in every parish in Scotland. Scarcely was there a castle, tower, or hamlet from which there were not flowers “weeded awa.” Amongst the men of note who fell on that bloody field was Sir Alexander Stewart of Garlies.

p 40

At this period Galloway was in a very disordered state, and law was very partially administered. A reference to “Pitcairn’s Criminal Trials” will show that those who ought to have set an example were most frequently the originators of disturbance. No crime was too serious but its pardon could be bought, if the money could be raised. Frequently in the assize for trial of prisoners at justices ayre at Kirkcudbright or Wigtown appear names of Minnigaff lairds, but they were, like Caesar’s wife, above suspicion.

About the middle of the sixteenth century the Gordons of Lochinvar seem to have been the great governing family, In 1555 Sir John Gordon of Lochinvar was nominated by the Queen, Justiciary of the Lordship of Galloway, and he received a renewal of his commission from King James in 1587.

The Gordons identified themselves with Queen Mary’s interests, and as they were powerful, both in Church and State, we presume it was to punish their adherents that immediately after the defeat of the Queen at Langside, Galloway was visited by the Regent Murray.

It is popularly, but erroneously, supposed that the old bridge at Cumloden Mill, usually called Queen Mary’s Bridge, obtained its name from the tradition that the Queen passed over it in her flight from Langside to Dundrennan. This supposition, as we have stated, is incorrect. Mary travelled through the Glenkens on her way to Dundrennan. During the course of the journey Lord Herries pointed out to her Earlston Castle, which had been the occasional residence of Bothwell, when she burst into tears at the memory of happier days. The name therefore of Queen Mary’s Bridge at Cumloden seems to have derived its origin more from poetic imagination than historical fact.

After the assassination of the Regent Murray in 1570, Queen Elizabeth sent down the Earl of Sussex and Lord Scroop to still further punish and overawe the friends of Mary in Galloway. – And although I am unable to trace from history any reference to these emissaries having ever been in the parish, it is not improbable that they may have been in Minnigaff, and from their being associated with the memory of the unfortunate Mary, may thus have been the means of identifying the name of Queen Mary with this romantic bridge.

During the minority of James VI., though the “toune” of Minnigaff does not come into national prominence, it was a frequent subject of discussion at the Convention of Royal Burghs. At this period Minnigaff was a place of some importance, and in which a good business was carried on.

It is interesting to learn that on the arrival of James VI. and his bride at Leith on 6th May, 1590, amongst the guests invited, Minnigaff was represented by Sir Alexander Stewart of Garlies. Sir Alexander, who had been created Lord Garlies on 2nd September, 1607, was in 1623 raised to the dignity of Earl of Galloway; his descent from the illustrious family of Lennox being assigned as the principal reason for raising him to the peerage.

About the year 1604 the first survey of the parish was made by the Rev. Timothy Pont. Of this remarkable man very little is known as to his personal history, nor is the precise date of his death recorded. A brief sketch of him and his works is given in The Scottish Nation, from which we learn that in 1608 he undertook a pedestrian expedition to explore the remote parts of Scotland. Bishop Nicholson describes him as a “complete mathematician and the first projector of a Scotch atlas, for which great purpose he personally surveyed all the several counties and isles of the kingdom.” The originals of his maps are preserved in the Advocates’ Library. They were ordered by King James to be purchased from his heirs, and Sir John Scott of Scotstarvet afterwards prevailed upon Sir Robert Gordon of Straloch to prepare them for publication. Their revision was continued by his son, Mr James Gordon, parson of Rothiemay, with whose corrections and amendments they were published in Blacus Atlas, under the title of Theatrum Scotiae.

Sir Herbert Maxwell, M.P., in his recent work, Studies in the Topography of Galloway, thus refers to Pont’s death: – “His death must have taken place between 1610 and 1614, in which latter year Mr William Smith was in occupation of the benefice of Dunnett, but minute as are the circumstantial details of many ignoble lives in all periods of our history Timothy Pont’s energetic soul passed away without record and no man knows where his bones are laid.”

Pont’s maps, finely engraved on copper, carefully coloured by hand, and enriched by quaint emblematical titles and emblazoned shields of arms, were published in Amsterdam. Some of the names in the maps have therefore assumed rather a Dutch complexion. That part of the atlas containing the parish of Minnigaff is called Gallouidae Pars Media, and comprises the district lying between Dee and Cree.

In this map is marked every castle, gentleman’s seat, farm, mill, or clump of trees, and the course of the smallest stream is shown – Calgow burn even. Each different object in the landscape is represented by a distinct symbol; a church by a cross on a pedestal, a mill by a millwheel, a castle by an enclosed space, hills and trees are shaded to bring their outlines into prominence. Thus at a glance, a bird’s-eye view can be obtained of the district as it appeared nearly three hundred years ago. It is surprising to note how many objects have now entirely disappeared from the face of the earth—even in this small speck of the universe – since the survey was first made in 1604. Certainly the names in many cases are still preserved in leases, but the small farms have ceased to exist as separate holdings. This is the case in many instances with farms once tenanted by those who were members of session—Heron in Drumnacht, M‘Harg in Terregan, M‘CauI in Waulkmill of Glenhoise, M‘Whanle in Cleckmalloch, Martine in Carsduncan, and many others.

A side-light is thrown on the state of society in Minnigaff about the beginning of the 17th century by the frequent references made to that “toune” in Pitcairn’s Criminal Trials. Under date of 23rd November, 1605, we find “Robert M‘Dowell and Johnnie M‘Dowell, sons to Peter M‘Dowell of Machirmoir, dilaitit of airt and pairt of the mutilatioune of Patrick Murdoch of Camlodden, and Alexander M‘Kie, his servant, of thair richt handis. Persewer Patrik Murdoche of Camloddene, Alex. M‘Kie his servand, Sir Thomas Hamiltoune (knycht), Advocat to our soverane lord, Prelocutoris for the pannell, Mr Alexander King, Peter M‘Dowell of Machirmoir, the laird of Mondurk, Robert M‘Dougall, Mereheand. Peter M‘Dowell of Machirmoir became pledge and suertie for Robert and Johnne M‘Dowellis, his sonnes, that they sall compeir befoir the justice or his deputes the third day of the nixt Justice air of the Sherefdom of Kirkcudbrycht, or sooner, upon fifteen days wairning to underly the law.”

It would seem that the jury empannelled to try these two young men of the period were in fear of being afterwards treated as had been Comloddone and his servant, for twenty-six of those summoned were “amercait in payne of ane hundreth merkis each for not appearing to pass upon the assize of the M‘DowelIs.”

Peter M‘Dowell would be very unpleasantly placed, as he was hereditary coroner of that portion of Galloway which is contained between Dee and Cree, and would thus be called upon to prosecute his own sons.

There are other cases in which the names of local lairds are frequently mentioned, but they are not directly connected with Minnigaff. “Slauchter” seems to have been a common crime in Galloway in the beginning of the 17th century, instances even occurring in the town of Monigaff.

In December, 1610, Patrick Hannay, Provost of Wigtown, who had married a daughter of M‘Kie of Larg, was shot in a fray at the Cruives of Cree by John Kennedy of Blauquhan. From the surroundings of the case it would seem that both gentlemen were considerably inflamed by liquor. On the 20th November, 1618, a Minnigaff laird was “dilaitit” of the “slauchter of Robert Gordon of Bairnairny, within the dwelling-house of Andro M‘Dowall mercheand in Monygoff, by running him through with his sword.” Through the influence of M‘Kie of Larg the affair was hushed up. Such were some of the startling episodes which took place in the parish during the earlier part of the 17th century.

About the year 1623 Peter M‘Dowell, who had built the Castle of Machirmoir, got into difficulties—perhaps through the bad conduct of his “sonnes”—-and lost both Machermore and Physgill.

The estate of Machermore now passed into the hands of John Dunbar of Enterkyne, parish of Tarbolton, Ayrshire, ancestor of the present respected owner of the property—Major Robert Lennox Nugent-Dunbar.

But we now approach one of the most stirring epochs in Scottish history, and in the crisis Minnigaff honourably bore its part. I refer to the struggles of the Covenanters for religious liberty. That wise fool, James VI., died on the 29th March, 1625, and was succeeded by his son, Charles I., a much more respectable man in many ways, but with faults of character quite as conspicuous.

Charles believed that he reigned by a divine right, and he had the courage to maintain his opinion.

He paid his first visit to Scotland in 1633, and gave the people there a taste of what he had in store for them, by keeping the Sabbath after the manner recommended in the Book of Sports.

This period of Scottish history is well described by the Rev. N. L. Walker, to whom we are indebted for the following information: – “Hitherto Knox’s Liturgy, as it had been called, had been in use where needed. It had been prepared to meet the necessities of past reformation times, when ministers were few and public worship could not have been maintained.

As vacancies were filled up by educated men, the Liturgy fell aside. But, of course, it regained its position under the Episcopal system, and this was the form which Archbishop Laud met with when he came with the King. That a high Anglican such as he should have been dissatisfied is not to be wondered at. He went home with the determination to provide the benighted Scotch with a better service book, and sure enough, what was meant to be a great boon to our nation in due time arrived. It arrived not in the bookseller’s shops to be bought by anyone who wanted it. It arrived not for delivery to the General Assembly to be examined and approved. It arrived with a sovereign law behind it, ordering every minister to provide himself at once with two copies on pain of deprivation, and directing its immediate adoption by all the congregations of the Church.” This was the last straw, and it broke the long-tried patience of the Scottish nation. Measures were at once taken to resist this attempt at religious intolerance. Now commenced that struggle between the King and the people, which did not end until the Stuarts, fifty years afterwards, were driven from the throne. Into the various phases of events during that terrible time – it is not my intention to enter at length; but only in so far as Minnigaff is concerned.

p 50

There is no page in Scotland’s history since the days of Wallace and Bruce calculated to excite a more glowing emotion of patriotism in the bosoms oi Scotchmen than that which relates the events of this period. The era of the Covenanters is a distinct epoch in Scottish history — it is a period presenting instances of Christian fortitude not surpassed in the history of the Church.

The leaders of opinion in Galloway at this time were fully aware of the important issues at stake in the struggle, and quickly formed a committee in connection with the central organisation in Edinburgh to co-operate with them in the maintenance of religious liberty.

The Minute Book of the War Committee of the Stewartry casts a faint light on events in Minnigaff in the year 1640. Lord Galloway and Sir Patrick M‘Kie, the laird of Larg, were the two gentlemen chosen to represent Monegoff — as it was then called — on the War Committee. Subsequently the Laird of Machermore was added. They were empowered to levy taxes on rents to furnish the sinews of war in the struggle between the King and the people The doings of this committee seem to have been in some cases more arbitrary than those which they wished to amend. Still they walked according to their light, and acted from honesty of purpose and for the best advantage.

It might be mentioned that the original Minute Book of the War Committee of the Stewartry is preserved in the Charter Chest at Cardoness Castle.

When the army of the Covenanters took the town of Newcastle from the King’s forces,- the troops commanded by Sir Patrick M‘Kie were particularly distinguished for their: bravery. In the engagement, however, Sir Patrick lost his only son, a brave aspiring youth, who, having seized the English General’s colours, was flourishing with them when, by mistake, he was slain by some of his own men. He was standard bearer to Colonel Leslie, and was the only person of note who fell that day on the side of the Covenanters, being much lamented by the whole army.

Twenty years afterwards, when the religious had changed into the political struggle, and the National Covenant and Solemn League were declared unlawful, Parliament appointed a committee for selecting the persons to be fined and the sum each person was to pay. – Amongst those marked out for punishment for having a mind of their own occurs the name of Patrick M‘Ghie of Largie, who was fined £260, and his friend and neighbour, Heron of Kirrouchtrie, who was mulcted in £600.

p 52

In the year 1662 a regular post between Scotland and Ireland—though only once a week — was established. The mails would in all probability be carried on horse-back from Minnigaff to Portpatrick. There is an old feu charter extant in connection with property in the village in which a reference is made to the Post Office building. In winter, when the roads were covered with ice, in going up steep hills the post was obliged to dismount and spread his plaid on the ice in order to give his horse a sure foothold. At this date the postage of a letter across from Scotland to Ireland was sixpence.

From this period on till the “killing times” we have no definite information as to what went on in the parish, but we do not suppose political or ecclesiastical affairs in Minnigaff were different from what was taking place in other parts of Galloway — and that was far from what was desired. Indeed, the greatest hardships were borne by the folks in Galloway until they culminated in the rising at Dalry on 13th November, 1666. – After this date the dogs of war were let slip, and Galloway became for twenty years – the happy hunting-ground of men of the most inhuman and infamous character.

Like neatly every other parish in the province, Minnigaff contains the. graves of martyrs. We can but briefly refer to the tragedy at Glentrool. The facts are thus set forth on the tombstone at Caldons: – “Here lyes James and Robert Duns, Thomas and John Stevensons, James M‘Clude, Andrew M‘Call, who were surprised at prayer in this house by Colonel Douglas, Lieut. Livingstone, and Cornet James Douglas, and by them most impiously and cruelly murder’d for their adherence to Scotland’s Reformation Covenants, National and Solemn League, 1685.” “In memory of six martyrs who suffered at this spot for their attachment to the covenanted cause of Christ in Scotland, January 23, 1685.

Erected by the voluntary contributions of a congregation who waited on the ministration of the Rev. Gavin Rowatt of Whitehorn, Lord’s Day, 19 August, 1827.” The tomb stands in a lonely marsh near the Water of Trool shortly after it leaves the loch of that name.

The site of the old house of Caldons, or Caldunes, where the martyrs were taken and put to death, is supposed to be marked by a shapeless heap of stones. This tragic event is referred to in the Macfarlane MS. description of the parish; written in the seventeenth century, and now lying in the Advocates’ Library —“And it is to be remembered at a house called the Caldons that remarkable scuffle hap’ned between the mountainiers and Coll. Douglas, at which time Captain Orchar (Urquhart) was killed. There was one particular worth the noticing, that when two of these people were attacked they got behind the stone dyke with their pieces cocked for their defence. Upon their coming up at them very unconcernedly one of their pieces went off and killed Captain Orchar dead, the other piece designed against Douglas wou’d not go off, nor fire, for all the man cou’d do, by which the Colonel, afterwards General Douglas, escaped the danger. There were six of the mountaineers killed and no more of the King’s forces but one dragoon. One of the poor people escaped very wonderfully of the name of Dinn or Dunn. Two of the dragoons pursued him so closely that he saw no way of escape, but at last flying in towards the lake the top of a little hill intercepted the soldiers’ view, he immediately did drop into the water all under the brow of the lake but the head, a heath bush covering his head where he got breath. The pursuer cried out when he could not find him that the devil had taken him away. Captain Orchar had that morning uttered a fearful oath, little dreaming that ere night he should have been so suddenly called hence.”

In Wodrow’s History of the Church of Scotland there is mention made of two brothers, Gilbert and William Milroy, who lived at Kirkalla during the persecution. Having fled their house in search of religious freedom, they were captured next day and brought before the Earl of Home at Minnigaff. Here they were examined as to their Church attendance, and the usual enquiries made as to their religious views. When they declined to answer they were tortured with burning matches and kept in the prison at Minnigaff six days, and the torture repeated daily. They were afterwards removed to Edinburgh, and after suffering great hardship banished to Jamaica. William’s ultimate fate is uncertain, but Gilbert was liberated at the Revolution and came home safe to his wife and relations, and was in 1710 alive and a useful member of the Kirk-session of Kirkcowan. The following traditional incident is said to have befallen the Rev. James Renwick of the town of Minnigaff.

It was known that a conventicle was to be held by him among the desert mountains in a place the name of which is not given, and to this place the leader of a party of dragoons repaired with his men for the purpose of surprising the meeting and seizing the preacher. Mr Renwick and his friends, by certain precautionary measures, however, were made aware of their danger, and escaped. In the eager pursuit the commander of the troops shot far ahead of his party in the hope of capturing by his single arm the helpless minister on whose head a price had been set. Mr Renwick, however, succeeded in eluding the pursuit, in wending his way through the broken mosses and bosky glens, and came in the dusk of the evening to Minnigaff and found lodgings in an inn in which on former occasions he had found a resting place. After a tedious and fruitless chase through moor and wild, the same leader of the troops arrived at the same place, and sought a retreat for the night at the same inn.

It appears to have been in the winter season when the occurrence took place, for the commander of the party feeling the dark and lonely hours of the evening hanging heavy on his hands, called the landlord, and asked if he could introduce to him any intelligent acquaintance with whom he might spend an hour agreeably in his apartment. The landlord retired and communicated the request to Mr Renwick, and whatever may have been the reasons for the part which on this occasion he acted, Mr Renwick, it is asserted, agreed to spend the evening with the trooper. His habilements would no doubt be of a description that would induce no suspicion of his character as a non-conformist minister, for in those days of peril and necessity there would be little distinction between the plain peasant and the preacher in regard to clothing. It is highly probable that the soldier was a man of no great discernment, and hence Mr Renwick succeeded in managing the interview without being discovered by the person in whose presence he was, and without his being suspected by others who might happen to frequent the inn. The evening passed agreeably and without incident, and they parted with many expressions of high satisfaction and good will on the part of the officer, who retired to sleep with the intention of resuming his search in the morning. When all was quiet in the inn, however, and when sleep had closed the eyes of the inmates, Mr Renwick took leave of the landlord, and withdrew in the darkness and stillness of the night to the upland solitudes, in which to seek a cave in whose cold and damp retreat he might hide himself from the vigilance of his pursuers.

When the morning came and the soldiers were preparing to march, the commander asked for the intelligent stranger who had afforded him so much gratification the preceding evening. The landlord said he had left the house long before the dawn, and was far away among the hills to seek a hiding place. “A hiding place !” exclaimed the leader. “ Yes; a hiding place,” replied the innkeeper. “This gentle youth, amiable and inoffensive, as you have witnessed him, is no other than the identical James Renwick after whom you have been pursuing.” “James Renwick. Impossible! A man so harmless and so discreet, and so well informed, if he is James Renwick, I for one at least will pursue his track no longer.”

The officer immediately marched away with his dragoons, and searched the wilderness no more for one of whom he had now formed so favourable an opinion.

Such were some of the incidents in the “killing times,” though happier days were in store for Scotland, but not till the last of the Stuart Kings had left the throne.

William, Prince of Orange, landed at Torbay on the 5th November, 1688, and next year turned his attention to religious matters in Scotland.

p 60

While tolerating all sections of the Church, he declared his intention of helping that form of Church Government which he understood would be most in harmony with his administration and the wishes of the people. The first step towards the reconstitution of the Presbyterian Establishment was the abolition of the Act of 1669, which had made the King head of the Church. The next was to restore the surviving ministers, who had been ejected for not conforming to Episcopacy after the Restoration.

The Episcopal Clergy, who had been the authors of much of the sufferings of the people in this part of Galloway, had now to feel the effects of retaliation. “Never,” says Dr Story, “were enormous wrongs so leniently retaliated. Never in the day when power had passed from the oppressors to the oppressed was the oppression as lightly revenged.”

In the parish of Minnigaff the popular enthusiasm vented itself as in several hundred other parishes in “rabbling the curate.” The conduct of the rabbler in turning the Episcopal curate out of the manse is not to be justified, but when all is considered — no violence was used — it was perhaps the most expeditious manner of getting rid of one who had always been looked on as an intruder in the parish. These “evictions” took place in the winter of 1688, but what became of the Rev. J. Jonkin after he was ousted from Minnigaff manse I have not learned.

The first meeting of the Presbyterian clergymen within the bounds of the Synod of Galloway, took place at Minnigaff on the 14th May, 1689, when the Rev. Robert Burnet was minister of the parish.

Few of the ministers who had parishes prior to the Restoration were present, but there were numbers of preachers from Ireland, and these were in several instances installed in vacant parishes. The following overture drawn up at the meeting in Minnigaff was forwarded to the General Assembly of the Church – “That there be a general day of humiliation kept through the whole kingdom with public confession of the general defection in order to the purgation of the said defection and healing the divisions in the land.”

A few years after the Revolution Settlement an event happened which produced a considerable sensation in a large part of Galloway. The Rev. John MacMillan, at one time chaplain to the Laird of Broughton, was no sooner ordained minister of Balmaghie than he began to differ from the settled form of Church Government. He influenced other clergymen, and they presented a petition to the Presbytery for an enquiry into Church affairs generally. This the Presbytery looked on as a new form of religious monomania, and desired him for the sake of peace to let bye-gones be bye-gones; but no, MacMillan persisted with his “protestation” till the Presbytery looked at his conduct as insubordinate, and at last deposed him from his parish. After the struggle between him and his successor had continued for fifteen years, MacMillan retired and became the founder of the sect of Macmillanites. He is said latterly to have had his residence at Barncaughla, but the number of his followers in the parish was limited to two or three families. He preached occasionally in different parts of Galloway, and at home but seldom.” He died at Broomhill, in the parish of Bothwell, on the 1st day of December, 1793, in the 84th year of his age.

In the meantime a rival town to Minnigaff had sprung up on the west side of the River Cree. A few particulars concerning the early history of Newton-Stewart may here appropriately be introduced.

William Stewart of Castle Stewart obtained a charter from Charles IL, dated the 1st July, 1677, for founding a Burgh of Barony to be known as Newton-Stewart, the site of Newton-Stewart being formerly known as Fordhouse.

He also obtained the right of holding a weekly market and two annual fairs. At first the town consisted of only a few houses, which were built by the superior as the nucleus of the future town. As Minnigaff began to decline Newton-Stewart increased in prosperity. The building of the bridge connecting the military road from Dumfries to Portpatrick, and thus obviating the necessity of fording the Cree, was a great advantage to the rising town; but it seriously affected the prosperity of “Auld Minnigaff.” It is said that rats desert a sinking ship; it is also true that skilled labour leaves a declining town. A short time previous to the building of the bridge we find one of our bailies, John M‘Cellan, had left Minnigaff and was a member of Penninghame Kirk-Session. No doubt the building of the bridge did away with his income, for his tombstone in Minnigaff Churchyard informs us that he was “ once boatman at Newtoun-Stewart.”

The market in Minnigaff still continued to be held, and was attended by many people from a distance for the purchase of meal and other necessaries.

The food of the common people shortly before the beginning of last century consisted of the meanest and coarsest materials, being both dirty and ill cooked. Those lived comfortably who could obtain a sufficient supply of brose porridge and sowens, perhaps made of meagre grain dried in pots and ground in querns with greens, or kail occasionally boiled in salt and water. The old kiln pots are frequently to be met with in the vicinity of farm houses, but they have now entirely fallen into disuse, and as for quern mill stones they are now objects of antiquarian interest. By this method of drying and grinding meal it was quite possible in a short time to place on the table steaming cakes which had been growing corn an hour before.

The common people had as yet acquired no luxury except tobacco, though the higher classes were in possession of what was then thought the luxuries of life. The Kirk Records towards the latter end of the 18th century testify to the proneness of the folks in Minnigaff to perpetuate the national failing.

By Act of Parliament in 1696 the days for holding the weekly market and fairs at Newton-Stewart were changed from Friday to Wednesday.

In 1784 the lands of Castle Stewart, along with the town of Newton-Stewart, were purchased by William Douglas, of Messrs. Douglas, Dale, & Co., who, after erecting an extensive cotton mill, changed the name of the town to Newton-Douglas. This name is yet to be seen on clocks which were made in Newton-Douglas at this date. It also occurs once on a tombstone in the old churchyard of Penninghame, but strange to say it is not to be found in Minnigaff Churchyard.

As it was thought by the local landed gentry that an increase of millworkers in the district meant a decrease of game, they used their influence against the success of the cotton mill. It thus fell into decay, and was eventually purchased by Lord Galloway in the beginning of the last century for about five per cent. of the original cost of £20,000. After the purchase the name of the town was again changed back to Newton-Stewart, and it is thought that the market day was also altered to Friday, and has since so continued.

But we must return to the Minnigaff side of the Cree, and may, in passing, refer to that old standing grievance — the custom levied by the town of Wigtown on certain farm products crossing from the Stewartry to Wigtownshire or vice versa. The Royal Burgh of Wigtown, which was raised to that dignity by David II., obtained by charter from James II. in 1457 the right to levy a toll on all cattle, sheep, pigs, and wool passing over or across the river Cree, where it bounds the County of Wigtown, Charles II. renewed this charter in 1662, the benefit of which Wigtown continued to enjoy till a few years ago. The annual income to the Burgh from this source averaged about £70; the custom at Creebridge generally produced £50 per annum; whilst the railway company paid £20 for their bridge across the river at Parkmaclurg. In the rising of 1715 no one in the parish seems to have been particularly interested, but it is traditionally reported that this is the time at which the first of the Erskines came to Minnigaff

Two brothers of the name, who had fled for safety from the Highlands after the disbanding of the rebels in 1716, came to Galloway. One settled in Kirkcudbright, the other found his way to Minnigaff; and having ingratiated himself into the favour of John Roxburgh, — the resident locksmith in Creebridge — eventually married his daughter and succeeded to the business. From him are descended the Galloway Erskines, most of whom still follow the ancestral trade of smiths. The late Mr James Erskine, gunmaker, Newton-Stewart, universally known as the inventor of cartridge loading machines and patents in connection with breech-loading guns, was a Minnigaff man of whom the parish may well be proud. It is also said that Prince Charlie’s secretary is buried in Minnigaff churchyard, but this is mere tradition.