Introduction by Barry McKee

I was born on a “farm” at Eagle Lake in 1940, but my family moved south when I was age 2, so I have no memories from there. Two cousins, Bill and Ross, moved there in 1931 with their father, David McKee, to help their grandfather Andrew after his wife died. Bill and Ross have contributed their Machar Township Memories to this page: see Part 1 and Part 2 below. Recently, I have found a short history of Machar Township which shows the struggles of settlers there who had expected farmland but found granite instead! This is now Part 3. The last section, Part 4, describes the Upland Community in more detail.

The pictures in the gallery below are Bow and McKee early pictures – click to enlarge!

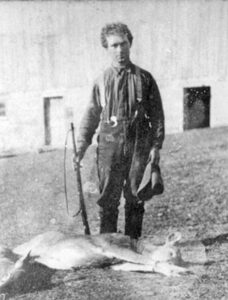

Machar Twp. Alex Bow with Deer – 1910

Machar Twp. – Bow Family and Friends on Car – 1920

Machar Twp. – Bow Family Farm – 1930

Machar Twp. Abandoned McKee Homestead – 1970

Machar Twp. – Old Bridge at Narrows – Eagle Lake

Old Nipissing Road – 2003

Bow Cemetery at EagleLake -2003

Bow Cemetery at Eagle Lake – 2003

Former McKee Farm, Eagle Lake – 2003

Part 1 MACHAR MEMORIES – – by Bill McKee, 2011

Chum’s Early Part

My tale begins with two events of which I have no personal recollection. The first was being born in Toronto in November 1930.The second was moving, in the Summer of 1931, with Harold and Mother and Dad, to live with our grandfather, Andrew McKee, on the farm at Eagle Lake, in Machar Township, Parry Sound District. The next event involved me getting separated from the family while berry-picking on the neighbouring farm, and wandering into the thick woods. I would likely have been only one or two – so disaster impended! Fortunately, the farm collie dog Chum stuck with me and, as the story goes, continued to bark ferociously to attract the others to my rescue!

Chum remained a much-loved member of the family until we departed the farm in 1942.

Winter Times

Through the 30’s our Dad was absent through the winter months when he was employed as the company clerk for the Standard Chemical wood-cutting camps. They were located on the western borders of Algonquin Park, east of South River. It was employment that paralleled the winter treks to lumbering camps, a part of local culture and history. Grandfather was at the farm with Mother and was able to handle the farm chores, with some help from Harold and me. I recall that he was a hard and short-tempered taskmaster! We did have cows to be milked by hand, a skill that I acquired. I remember one cow was named Bessie and she was a good milker.

Depression Years

My recollection of the 1930’s depression era will always remain the extreme reluctance of the rural folks to get in a situation of accepting “relief” assistance, that being regarded as somehow dishonorable. We raised cash through the summer by selling our garden produce to the cottagers at the Lake – the Swartz’s from Buffalo, and the Kuntz families from Waterloo. Their fine cottages, in the traditional creosoted-log style, would have easily qualified for a present G-8 grant!

These times also marked the births at the farm, of Ross (‘34) and Earl ’38). I recollect Ross as a newborn in the living-room. It was March and heat from the parlor stove was required. I remember Earl being newborn in the ground-floor bedroom.

Church Events

Sunday afternoons we went to the United Church Service and Sunday School, near the Eagle Lake Narrows. I remember that our Aunt Annie Bow – who had in earlier life been “in service” in England before marrying Uncle Tom -was the teacher. The minister, Rev. Howard Eaton, was distantly related to the T Eaton store family and I recollect that he loved to work some reference to cars and driving into his sermons! A church-sponsored activity I remember was the annual Dominion Day or July First Picnic at the Narrows. Fowl Suppers and Christmas Concerts were held at the church. Another event that I remember was our grandfather’s funeral service there, in May, 1940.

S.S. No. 3 School Days

I started attending the one-room school on the Eagle Lake Road in September of 1935 when I was only 4 (5 in November). I was allowed to sleep in a corner in the afternoon, as there was no way for me to follow the bush trail home by myself. I had to wait until Harold finished the full school day at 4:00 pm. My teacher was Lily McKee who was not a relative. She subsequently married into the Tough family, becoming Mrs. George Tough.. The next year, still at five, I moved into regular Grade l (it might still have been called Junior First then) – and continued my academic career. I was a school custodian, first with Harold, and later with Ross, after he started school in September, 1940. In winter, that meant getting to the school early enough to have the basement furnace going, started from the previous afternoon’s stoked log, or relit if that had burned out, without filling the upstairs with smoke! In winter travel was on skis —downhill in the morning, but uphill in the afternoon! I recollect an incident during the “spring fever” time of early I941, when the entire group of students played “hookey” en masse. The teacher, a Miss Jean Sampson, was late in arriving. A note was fabricated and posted saying that there would be no school on that date. But unfortunately, the day involved, Tuesday, was mis-spelt “T e u sday”, and the jig was up!

Visiting Royalty – 1939

Modern visits by Royal personages are a reminder of the trip that students from along the railway line made to Sudbury in May 1939, to celebrate the Tour of George VI and Queen Elizabeth. I recollect that Harold and I started out very early one day and arrived back near dawn the next. One clear memory I have is of people having paper periscopes, with appropriate mirror arrangements, enabling them to get a view over the crowd in front of them. No Jumbotrons in those days!

Wartime

Activities recalled from the early years of WW II include the search for and collection of scrap metal and rubber tires. Some things, including sugar and gas, were rationed. Harold and I were involved in getting supplies by horses and sleigh, to the miners who were gathering mica, an insulating material needed for wartime electronic equipment, from a mine at Rat Lake. Wartime news reports that I remember clearly were those of Dieppe and Pearl Harbour.

“Over the Hills and Far Away”

We left the farm and Machar in September 1942 because work was available for Dad and Harold in the war munitions plant in Nobel, at the other end of Parry Sound District. Dad had gone there earlier, and it was a bit like the days of his bush camp clerking. Sadly, we could not take our elderly dog, Chum, with us and he had to be put down.

Miscellaneous Machar Memories

- Sleeping downstairs on cot next to wood stove and window. Awoke one morning to find a deer looking in the window at me. It ran off across the field. Also, awoke to find ice covering the pail of water that had been left overnight.

- Tree houses among the trees running alongside the farm field.

- Going to the Kuntz—Swartz cottages and seeing all the toy soldiers, etc. arrayed on the moss beside the lakeshore.

- Going through the bush to the school house and returning – not sure if alone or not on the trip back. Seeing a bear.

- In the car, a black enclosed Chev, on going up a steep hill, having to get out and place logs behind the back wheels after Dad had driven it a few yards. Activity repeated until the top of the hill was reached. Another time, going up laneway and black bear in front of car.

- Trip(s) to North Bay to visit Uncle Alec, Aunt Kitty, and Don McKee. Given liquorice whistles.

- Car stored in barn: seemed like a 1920’s open touring car; green in colour.

- Visiting Tom Bow and Aunt Annie by going through bush to their farm on the Eagle Lake road.

- Skis — handmade with leather straps to put boots in.

- Cows — being put on top of cow when brought back from pasture.

- Large black kettles — scalding a pig.

- Inside house — a globe of the world made of two pieces of cardboard that attached through slots in each piece.

- Harold going into the bush with Chum when we were leaving the farm to go to Nobel. Harold had rifle. He would not let me go with him. Chum did not come back with Harold.

Part 2 MACHAR MEMORIES and OTHER THINGS – – by Ross McKee, 2012

The Slippery Slope

I have recollections of Bill and I, and possibly Harold, having skis made for us by an elderly gentleman living in a modest cabin at the back of the Preston lands north of our farm. It seems to me his first name was Joe. His last name escapes me but it was either Hoetla (sp) or Oakley as I recall. The skis were hand-made out of birch or maple or some similar type of wood and they were very narrow with rawhide straps in the centre which were used as foot holes. They were well-made and served as a means of winter transportation to the schoolhouse and home. I cannot remember if “Joe” ever worked for anyone but may have been employed in some way at the mica mines north of his property bordering Rat Lake. He was of Serbian or Slavic decent.

Barnyard Capers

When the haying was done and the crop was placed in the barn each year it created very high stacks. Bill and I used to climb up on the centre beams of the barn and proceeded to jump from the beams into the hay mows. A seemingly harmless activity, we thought; however, we probably did not think of potential harm from pitchforks or other farm tools that might have been left in the hay mows. Oh well, fun was fun.

I also recall helping with the various chores and particularly the milking of our small herd of cattle. Bessie was everyone’s favorite cow, however, I believe we did have another good milking cow named Judy but I may be wrong on the name.

Visit to See Quints

On one occasion the family went to Corbeil to see the Dionne Quintuplets. This was probably sometime in 1939 as I was five and this was the same age as the quints as they were born in May of 1934 whereas I was born in March of that year. They were in an enclosed play area with a wire fence around the area and with glassed in areas for people to observe them. No one was allowed to speak to or be in contact with the girls.

The War Years

On December 7, 1941 the attack on Pearl Harbour occurred. I recall hearing the news of this attack on our battery radio while in bed with my brothers. Our bedroom was heated by the presence of only the stove pipe running through the room and ceiling from the wood stove in the main room below. A pretty unsafe condition I would say, however, it was the way it was for many rural homes at that time. lt was central heating in its most primitive form.

I can remember at our Aunt Bessie’s farm house in August 1942 when the Dieppe invasion by the allied forces occurred in France and we heard about it on a radio while having dinner.

The Church and Events at the Narrows

I can recall that often after church we would go over to the sand banks near the church and use large stones to plug up the holes in the banks that were made by swallows.

The July 1 annual picnic was always a long awaited event each year with the wonderful picnic suppers and playing of games and races conducted. A softball game was held each year at the ball field next to the church where young and old joined in the event.

S.S. #3 School Days

I started my schooling at the small one room school house located at the end of our farm road on the opposite side of the Eagle Lake Road. During the winter months when I was in Grades 1 and 2 I had helped Bill in starting and firing the furnace for the school. This required us to be at the school quite early each winter morning in very cold, freezing temperatures. There was an open type of large register to heat the room located at the middle of the floor and when it got too cold in the room we all sat around the register to keep warm.

I recall being a bit mischievous on one occasion and was responsible for putting one of the girl’s pigtails in the inkwell on my desk. I think it was Daisy Smith and she was not impressed over my prank.

I also remember once when Bill and I were returning from school we came across a large black bear standing in the clearing along the trail not far from our house. We froze and were unsure what to do but the bear looked around then ambled off and we moved to the house at a very fast clip!

North Bay Hospital Stay

I vaguely recall my stay at St. Joseph’s Hospital in North Bay in September and October 1941, when I had emergency surgery for a ruptured appendix. As I was so sick from the events of the surgery and taking heavy doses of sulfa drugs (prior to discovery of Penicillin) I can not remember very much of my stay at the hospital. I do recall, however, the wonderful care provided by the nursing sisters at the hospital. I was off school for some time and not returning until into December of that year.

Trips to the “Big City”

Occasionally, during the summer months mainly, we would go to South River with mother and dad to buy certain staples used for baking, etc. such as flour or sugar, before it was wartime rationed. While there we may have been treated to some candy at the General Store. We did have a small amount of earning accumulated from the farm chore of picking potato beetles from the plants. It seems to me we were paid something like 2 cents for a full pickle jar. Not exactly union wage, however, it did create some incentive and gave us money to buy candy.

Our Days in Nobel

As I was aged 9 – 12 during the family’s time at Nobel there are a few things that come to mind such as:

- playing touch football at the field in front of the community centre

- having a couple of friends and school chums whose names, as l recall, were Robert Ford and Peter Maule

- delivering papers (Toronto Star) to homes on the Nobel Road in adverse weather

- a teacher by the name of Henry Coventry (a short gentleman with rather odd habits)

- a big fire at Parry Sound harbor occurring and concern of a potential large explosion

- seeing Harold in his army uniform when home on leave in December 1944

- I remember going to Parry Sound on Saturday afternoon by bus to “hang out” as they say

- like Earl, I recall the fishing trips with Wilfred Burridge and the experience of trolling on Georgian Bay around the Thirty Thousand Islands.

Part 3. Machar Township, 1900-1950

(from Ragnarokr)

http://www.ragnarokr.org/index.php-title=Machar_Township,_1900-1950&action=edit.html

https://www.eaglelakenarrowscountrystore.com/new-page-1

Machar Township: The boom fades.

The twenty years between 1880 and 1900 were boom years for Machar Township. Settlers arrived from the south just as the timber companies arrived from the north. Construction began on the Grand Truck Railway in 1883 and by 1886 the railroad had reached the future site of the village of South River. The economic focus of the area quickly shifted from the colonization roads to the railroad. Log drives on the South River became obsolete. By 1900 the old growth white pine had been cut and the large lumber companies left the area. Also, by then, many of the settlers had returned to southern Ontario or gone to western Canada seeking better land. The farmers who remained adjusted their operations to the soil and climate of the region. After 1903 the Grand Truck Railroad was extended to western Canada but a competing railway laid from Washago (just south of Severn Bridge) to Sudbury siphoned off much of the traffic that was previously routed through South River. Sawmills, the most important of which was a large mill in the village of South River, replaced the timber companies. Despite the jobs created by sawmills and a steadily growing tourist trade, the township fell into a decline from which it has never recovered.

Machar Township: The farm economy

The majority of the population of Machar Township lived in the village of South River and worked in the large sawmill there. Most of the rural inhabitants were subsistence farmers who raised a variety of crops on 100 or 200-acre lots. They supplemented their farm income with industrial work when they could find it. Most kept cattle, pigs, chickens and sometimes sheep. Their staple foods were porridge, turnips, potatoes, salted pork, beef, beans, molasses or corn syrup, tea and pastries. They supplemented their diets with venison, wild berries and garden produce.

The farmers planted hay grass in their lower lying, wettest fields and harvested crops of hay two or three times during the summer. The hay was field dried, stored in the upper floor of large barns built near the farmhouse and used for animal fodder. Oats were planted in drier fields and used for the family table and for animal rations. The oat straw was used as animal bedding and as stuffing for the straw ticks that sufficed for mattresses. The climate was too cold for field corn but corn was grown in the garden for roasting ears along with a variety of other vegetables. Turnips, beets, oats, cabbage and potatoes were about the only field crops that were not susceptible to damage by early frosts. Farmers living on Bunker Hill, Cole’s Hill and the Uplands community were less likely to feel the effects of early and late frosts and they planted orchards of apples, plums, butternuts and grapes. Wild berries such as blue berries, raspberries, ground blackberries and chokecherries were harvested in season and kept for home use or sold to a local buyer for shipment to North Bay or Toronto.

A minority of farmers sold potatoes, strawberries, milk, cream, maple syrup or some other product in commercial quantities. In the 1940s, the Machar Potato Club sponsored field competitions to encourage potato cultivation and until the mid-1970s several farmers specialized in growing potatoes. Between 1920 and 1950 Alex Bow and his son sold thousands of quarts of fresh strawberries annually from their farm in the Uplands Community. Other men sold strawberries in the village of South River and, in the 1970s, a community of Seventh Day Adventists sold strawberries and tomatoes from their farm north of Bunker Hill. For many years there was a stockyard in South River or Sundridge where animals were bought and sold. The winters were too long to make beef cattle profitable but a few farmers had small dairy herds and most farmers kept a few milk cows. Steers and any milk cows that failed to produce calves were sold. In the early 1920s farmers from Machar Township drove their surplus animals down the Muskoka Road to cattle pens near the railroad station in Sundridge. There a broker sold the cattle to Dominion Packers in Toronto. In later years the stockyard was relocated to South River. By 1900 South River had a resident butcher who had a slaughterhouse a mile west of the village on Spiessman’s Hill. He and the butcher from Sundridge purchased cattle and pigs from local farms for cash and sold the meat locally. Farmers in rural Machar Township slaughtered their own cattle and sold or bartered the meat to their neighbours and relatives. In the 1920s and 1930s Art Edwards, who had worked as a butcher in the lumber camps, sold mutton to cottagers from his farm on Edward’s Hill in the Uplands community. By the 1970s farmers were carrying their livestock to a licensed slaughterhouse in Powasson.

Many farmers sold milk and cream to their neighbours when they could find a buyer. In 1910 an enterprising dairy farmer left Machar Township and walked with his herd fifty miles to North Bay where he started the Maple Leaf Dairy. During the 1930s and 1940s dairymen carried their cream cans to the railroad platform in South River where the cans were picked up and sold in Toronto or North Bay. The farmers fed the skimmed milk to pigs until in the 1930s the Blue Ribbon Dairy opened in Sundridge and farmers from the whole region were able to sell bulk milk there. Beginning in 1932 Harvey Pinkerton Sr., a teamster for the W.G. Tough sawmill, began selling quart bottles of his own brand of milk door-to-door in and around South River. He carried his milk to Sundridge to be pasteurized until in 1955 he opened Johnson’s Dairy on Highway 11 near South River. After the Ontario Milk Marketing Board began regulating the sale of milk, dairying provided a reliable income and there were several diary farms in the township between 1950 and 1980.

The stone ridges of Machar Township provide an excellent environment for the rock- or sugar-maple tree. The early settlers brought maple sugar-making equipment with them and almost every rural household tapped a few trees for their own use. Local farmers were tapping as many as 500 trees as early as 1925 and in the 1970s several producers were making syrup from between 1,000 and 1,400 taps each. A history of Machar Township that was published by the Township in 2000 listed 13 local farmers as having had commercial sugar bushes over the years. Much of the syrup was retailed to the same customers in southern Ontario year after year and the surplus sold to wholesalers. The maple syrup season occupies only a few months of the year and no one in Machar Township relies on maple syrup for a major portion of his income. Preparations for making the syrup usually begin in February and clean-up is finished by the end of May. The intensive part of the sugaring off season lasts from the first thaw in March until the deep snow has melted six or eight weeks later. During the short sugaring season sap flows intermittently only on warm days following cold nights and there may be no sap to gather and boil for days on end.

A similar seasonal activity that brings some income to Machar farmers is the annual deer hunt. The white-tail deer that inhabit Ontario are giants of their race and they were often plentiful in Machar and the surrounding townships. As early as 1920 local men built and maintained hunt camps to accommodate hunters from southern Ontario. Some of the camps are located on land west or east of the township that is leased for this purpose. Other local men served as hunting guides or hosted groups of hunters in their homes or in bunkhouses nearby. The deer season lasts for only a few weeks in November and the hunt camps are often booked years in advance by hunt clubs in southern Ontario. Often friends and relatives from southern Ontario use the occasion of the deer hunt to visit local families and join the men of the household to form a hunting party.

Machar Township: The non-farm economy

When the first settlers arrived there were no roads in the township. The settlers had to make them. The surveyor had clearly marked road allowances and, since the settlers fully expected that the township would one day be densely populated, they carefully avoided cutting roads through the surveyed lots. The settlers cut their trails to follow the road allowances even though the road allowances had been laid out in a grid pattern without regard for the township’s topography. In the pioneer days this was not a problem because most travel was on foot and the township roads were nothing more than paths through the woods. Little effort was made to avoid steep hills. On the other hand, the colonization roads were built by the government and were designed to handle vehicular traffic. These roads skirted extensive marshes and steep inclines but even they were impassable to wheeled vehicles for several years. The first, and for many years the most reliable vehicles, were sleighs. A few years after the Muskoka Road was put through carriages and wagons appeared but for many years wheeled vehicles were useful only during the six months between June and December. By June the mud was usually firm enough to support wagon wheels and in December the first heavy snowfall closed the roads to wheeled traffic.

The problem of road building occupied the township authorities from the very beginning. The Provincial government hired local men to work on the colonization roads and before 1900 pairs of men called Pathmasters were appointed to supervise road maintenance in their communities. In Machar Township, there were Pathmasters in the communities of Mandeville, Midford, Stewart Bay and Hamilton Lake. By 1910 road maintenance and construction began to be contracted out by the township government. In that year, George Smyth was paid one hundred dollars to clear and make a road that ran west of Eagle Lake from what is now Eagle Lake Road to the Boundary Road with Strong Township. Before 1938 the Township hired a road superintendent and a crew of men to maintain the roads. By then much of the road system constructed prior to 1900 had been abandoned because the road was either not suited for cars and trucks or the inhabitants had moved elsewhere. The remaining township roads consisted of straight sections that followed the road allowances and a few newer roads that cut across lot lines to avoid steep inclines, rock outcroppings and swamps.

Post offices were appointed in nine locations in and around the township and this provided a small but steady income for a few families. After the railroad arrived the mail come to the post office in South River by train and was delivered to the rural post offices on Tuesday, Thursday and Saturday. The rural post offices were located in either a storefront or a private residence. The first post office was at Peter Shaughnessy’s store in the Uplands Community at the corner of the Muskoka Road and the path to South River. Around the turn of the century there were six post offices in the township scattered about four or six miles part. Sometime before 1936 the rural post offices were closed. Thereafter a mail carrier picked up the mail at the Post Office in South River and delivered the mail directly to each farmer’s mailbox on Monday, Wednesday and Friday.

The first school in the township was built in 1878. Five others were built in 1893 and 1894. In 1902 a seventh school was opened. In 1900 there were 32 students in the rural schools and 159 attending school in the Village of South River. The Township paid for the construction and maintenance of these schools. Each school consisted of one classroom with a wood burning stove for heat and a separate outhouse. These were originally log structures. The schools each enrolled between two and twenty students from grade one to eight and employed one teacher. The curriculum consisted of reading, writing, arithmetic and the geography of Ontario. When the students reached the age of 13 most stopped attending school. Only a few students continued beyond grade eight. Students wishing to continue their education had to leave the Township and attend a boarding school. The parents of the students stocked the school with firewood and each school was watched over by a group of trustees organized into a school board. The school board paid the teachers a small salary and the teachers, almost always single women, usually boarded with a family nearby. Beginning in 1920 these rural one-room schools were closed as the number of students declined. The Mandeville School closed in the 1920s when only one student enrolled for the coming year. The Uplands School closed in the late 1930s. In the 1950s the four remaining rural schools were closed and the students were bused to a consolidated school in the Village of South River. In 1961 the remaining rural school buildings were sold to private buyers.

The number of farmers who were able to live from the proceeds of their farming operation or who were lucky enough to have a source of income from the Township, the Post Office or the schools was relatively small. Most farmers in Machar Township supplemented their incomes by working in some aspect of the sawmill industry.

The logging camps run by the J.R. Booth Company were designed to operate in wilderness areas and were practically self-sufficient. There is little evidence that the men working for the timber companies were also settlers in the township. However there was frequent contact between the settlers and the logging camps. The settlers sold eggs, butter and milk to the camps and they carried cut logs to the company sawmills to be milled into planks for their cabins. Conflicts arose between the settlers and the timber company because the white pine timber had been reserved by the Crown and sold to the Company. The timber company had the concession to cut all of the white pine but the terms of the land grants allowed the settlers to cut enough timber to construct a homestead. This confusing situation resulted in disputes over who owned what logs. Representatives of the J.R. Booth Company attempted to, and sometimes did, seize logs cut by the settlers. In 1876 the Company confiscated 440 of 500 logs cut by a settler in Machar Township. He had tried to barter some of the logs to the Company sawmill in exchange for cutting the remainder into dimensional lumber. On another occasion company men stamped the company mark on logs cut by another settler but the settler responded by sawing the marks off and standing guard over the logs. Before 1900 the timber companies had left the area and the existing sawmills were sold to their operators.

For the next three generations sawmills provided work for the people of Machar Township. Unlike the timber companies, sawmills cut the timber into dimensional lumber at mills in the township and then shipped the lumber on the railroad to markets in eastern North America. The mills hired local farmers and their teams to work at the logging camps during the winter months. A much smaller number of men worked throughout the summer milling the logs harvested during the previous winter. The logging operations of the sawmills were organized similarly to those of the timber companies with the men housed and feed by the company. Working men, skilled and unskilled alike, moved in and out of the area to work in these sawmills. Some settled in the township. Gradually an economy was built around seasonal work in the woods during the winter and farming during the summer. For the next fifty years this work cycle was characteristic of life in Machar Township.

In 1876 the JR Booth Company installed Shannon’s Sawmill at the Eagle Lake Narrows and in 1880 Dundar’s Mill at Sundridge, possibly to service the needs of the incoming settlers. However the focus of the company was the export of whole logs to Europe. In 1885 the company continued to make improvements to the South River to facilitate the floating of whole logs to the Ottawa River. In 1884 William Erb installed a sawmill near where the village of South River is today. Two years later the Grand Trunk Railroad was built just west of the river. For the first time, it was practical to ship milled lumber to markets in southern Ontario and beyond. In 1887 a new company called the South River Mercantile Company built a larger steam-driven mill above the existing dam. This mill manufactured railway ties, pit props, beams and fence posts with a crew of 100 men. The mill burned in 1900 and was replaced in 1901 by the South River Lumber Company.

The rebuilt mill operated 24 hours a day. In 1901 it produced 10 million board feet of lumber. In later years its capacity was increased to 125,000 board feet a day. A separate lath mill made 50,000 pine laths a day for use as backing for plaster walls and ceilings. A steam-driven generator provided lighting and a company store was built on Ottawa Avenue. A dummy or logging railroad was built to the east of the river and the company maintained logging camps near Algonquin Park. The company built housing for its mill workers in the area west of the South River, which, in 1907, was incorporated as the Village of South River. In 1904 the South River Lumber Company and the Turner Lumber Company merged to become Standard Chemical. Standard Chemical was the most important of the lumbering and logging operations in the township for many years. It continued to operate the logging railroad and the lumber camps east of South River and later operated a camp in the area of Hamilton Lake.

As the supply of mill quality logs declined, Standard Chemical shifted its emphasis to industrial chemicals. A chemical plant was built to manufacture charcoal briquettes, wood alcohol and acetate of lime. The chemical plant used cordwood as its feedstock. Standard Chemical purchased hundreds of acres of poor quality land from disgruntled settlers in the 1920s and 1930s and contractors were employed to cut the cordwood growing on the company’s lots and haul it to the nearest road. Standard Chemical also purchased cordwood from landowners and employed a large proportion of the workers living in the Village of South River. It rented housing to its workers and built gravel roads east of the township to access its timber concessions. It also maintained a winter road across Tyerman’s Marsh following the Old South River Road to access its bush lots in that direction. Standard Chemical gradually declined as a result of changes in the chemical industry. In the 1950s an international corporation purchased its parent company and most of its activities were moved away from South River. In the 1960s the only remaining product made at South River was pressed charcoal briquettes. By 1970 the South River charcoal plant had closed leaving a single caretaker to watch over the abandoned buildings containing the charcoal press.

Although Standard Chemical dominated the sawmill business east of South River, the western part of the township was home to numerous smaller sawmills. These mills were portable and were moved when the lumber within about a five miles radius had been cut. The sawmills were all driven by wood-fired steam boilers and almost inevitable burned down. An early planing mill was located west of the village behind the old agricultural fair grounds. It later manufactured windows, doors and coffins. It burned in 1907. Charles Robb had a sawmill where the Eagle Lake Golf Club is today. The mill was sold and moved prior to 1910. The piles of sawdust from the mill were burned in the 1930s. The mill operation left the East Bay of Eagle Lake in front of the mill full of stumps, treetops, culled logs and sawdust. In the 1930s, Art Edwards, who farmed the hilltop west of the Uplands School, cleared the beach along the shoreline and put in sand to make a bathing spot.

Another early timber man, Charlie Quirt, lost his sawmill to a fire in 1912 and purchased a mill belonging to a son of Charles Robb. This mill employed six men and a cook and had a bunkhouse where the crew lived. In 1914 Charlie Quirt sold this mill to G.C. Anderson. His brother, Harvey Quirt, stayed in the business and moved his mill to four locations within Machar Township over the next thirty years. After G.C. Anderson closed the mill on Eagle Lake, the bunkhouse was left standing and was used as a dance hall for a number of years. James Joy operated sawmills around Bray Lake during the 1920s and 1930s. He originally installed his mill on the west side of Bray Lake in 1916. This mill burned in 1919. His second mill was located near the first and it burned in 1921. This third mill was on the north end of the lake and burned in 1935. His mills employed about 30 men. Three different mills were located on the shores of Hamilton Lake. The first operated from 1890 until 1908. The last mill burned in 1947.

W.G. Tough owned four sawmills in four locations between 1925 and 1950. Three of the mills were in Machar Township. The last was located on Deer Lake in Lount Township and operated from about 1930 to 1950. Tough’s mills employed about twenty men and a cook. Between 1890 and 1970 some thirty sawmills operated in Machar Township, not including several two or three one-man operations.

Machar Township: The lumber economy

The work of the lumber companies was seasonal. Woods work was done during the winter and saw-milling was done during the summer. Extra men were hired in the fall to harvest the timber while snow was on the ground while a smaller number of permanent employees worked in the yard and in the sawmill processing the logs into sown lumber during the summer. Milling commenced as soon as the logs thawed in the spring and continued until around Christmas or until the supply of logs was exhausted. During the summer the sawmills employed from as few as two or three to as many as 100 men depending upon the size of the mill and the finished product being made. Each mill had a crew of semi-skilled yard workers who delivered the saw logs to the head saw. There a sawyer, operating a circular saw, cut the log into boards of whatever dimensions the market and log called for. The boards then passed to a trim saw that cut the boards into standard lengths. After leaving the trim saw the boards were graded and stacked. The stacked lumber was air dried and, in some mills, passed through a planer. A few mills further processed the lumber into doors and windows. Most mills custom-cut to the customer’s order whenever possible.

The men working in the sawmills were more likely to be full-time employees than the woods workers, some of whom were local farmers. The sawmill workers were members of the industrial working class and were often highly skilled in their trade. The mills were powered by steam machinery and employed one or two firemen to operate and maintain the boiler. The sawyer, the trimmer and the slab saw operators often maintained their own blades and sharpened their saws at the noon hour and before beginning work in the morning. The mills frequently employed a blacksmith and a millwright. A teamster kept the mules or horses in working condition and maintained the rigging used to haul the logs from the woods to the sawmill.

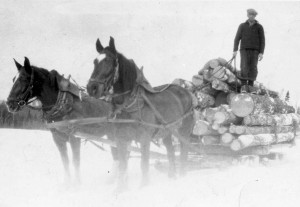

With the return of cold weather in the fall, and especially after the lakes and swamps were frozen over after Christmas, the woods work commenced. The work of harvesting the timber was greatly facilitated by the cold weather because the frozen swamps and lakes were used as roadways. The winter roads made by the logging companies are sometimes called swamp roads. These roads were used only during the winter months and, unlike the township roads, cut across property lines. Winter roads avoided hills and followed gentle inclines, lakes and swamps. They were designed for heavily-loaded sleighs pulled by teams of horses. Some of the winter roads were used to deliver lumber to the railroad station at South River. As early as 1894 a lumbering road was built as a shortcut in the Mandeville community. By 1900 there was a winter road from Rat Lake in the Stewart Bay community to the village of South River. In the 1930s a winter road ran from the south end of Deer Lake in Lount Township to East Bay on Eagle Lake and then through the woods to South River. This road crossed Eagle Lake south of the Narrows, left East Bay at lot 27, concession 4 and proceeded through lot 20, concession 3 to the 4th Concession Road and then on to South River. The public used these roads as well as the logging companies but the loggers maintained them. Winter roads were also built to access standing timber. The same roads were used year after year and many of the logging roads in use today were at one time cut as winter roads. After the roadway was cleared of standing trees the snow was packed down. Water was poured on the ruts to make it easier to pull the heavy sleighs. The men who iced the road worked from a tanker mounted on skids and pulled by a team of horses. Downhill slopes were sanded to prevent the logging sleighs from getting out of control. Workers called “beavers” (and supervised by a “buck beaver”) cut the road, “icers” put water on the ruts, “sandpipers” spread sand on the downhill slopes and “chickadees” kept the road clean by removing horse droppings and trash.

Crews of lumberjacks cut and hauled the logs out of the woods and to the roads. A chopper first found and marked the trees to be cut. Next a pair of sawyers felled the tree and cut it into lengths. Trail cutters limbed the logs and cleared a trail for the skidders. Teamsters skidded the logs to a place along the skid way called the cross-haul. At the cross-haul pairs of men called rollers used cant hooks to move the logs out of the skid way. The logs were then skidded to the road where they were loaded onto logging sleighs using a decking line or a jammer. The sleighs were pulled along the ice roads to the sawmill or to a body of water. These logging sleighs were from eight to fourteen feet long depending upon the condition of the road.

In the late 1930s many sawmills began using gasoline-powered trucks and motors although wood-fired steam boilers continued to power the sawmill until relatively recent times. The use of gasoline motors changed the logging operations and increased their efficiency. The mills no longer had to be moved every few years. In the 1940s trucks replaced teams of horses and it became practical to haul logs from 40 or 50 miles away. The Township had gradually rerouted the township roads to avoid especially steep hills and improved their surfaces. Winter roads continue to be used to access areas where no gravel road existed but their importance declined. Since the 1940s the Township regularly ploughs snow from the main roads and wheeled vehicles can be used even during the winter. (insert link to file 6.4, “Machar Township road 1930)

Machar Township: Woods work

The first cars in the township appeared around 1914. Prior to 1920 an automobile repair shop and two gasoline pumps were installed at a blacksmith’s shop in South River. By 1920 the blacksmith had become a Ford dealer and in 1928 he erected a larger repair shop for automobiles. Until the 1940s, the usefulness of cars and trucks was severely limited by the poor road conditions. Until the 1940s most local families used a team and a wagon for the muddy season in the spring, a team and a sleigh during the winter and a car in the summer. The poor roads isolated the farms and made it unlikely that travelers would venture into the rural parts of the township. The road from Highway 11 to Eagle Lake was over Bunker Hill and in the summer many cars had to be put in reverse to climb the steep lower part of the hill. In the winter it was impossible to get up the hill in an automobile. Travelers in the winter months parked their cars at one of the farms at Bunker Hill and continued to the lake on skis or snowshoes. As the roads were gradually improved so did the number of visitors to Eagle Lake.

In 1875 the surveyor wrote that Eagle Lake was a “very beautiful sheet of water surrounded by high hardwood land”. The lake quickly attracted the interests of travelers and tourists. In 1916 the owner of the South River Mercantile Company was the first to build a summer home on Eagle Lake. By 1920 parties of hunters were arriving in the township by train to hunt deer. Local families provided accommodation and acted as guides. In 1922 Henry Minor and a partner built a lodge on the south end of the lake to accommodate hunters and tourists. This lodge still exists and is until recently called the Hockey Opportunity Camp. In 1924 the engineer who operated the hydroelectric plant at South River before the War purchased the peninsula now called McLean’s Point and built a summer home there. Within the next two years, three other cottages were built on the lake and larger numbers of city residents were visiting the lake to bathe and fish. In the 1920s a group of local men organized an association called the Cottager’s Syndicate and purchased property on which to build weekend cottages. This property later became the Rainbow Bay Resort. In 1932 the Robb farm on the shores of East Bay was subdivided for cottages and 1938 Art Edward’s had his lakeshore surveyed into lots with each having 75 feet of lakeshore frontage.

Farmers with lakefront property gradually either sold out or subdivided and sold lots along the lakeshore. Existing farmhouses near the lake were sold and converted into summer homes. Sometimes local men built cottages and sold them but more often cottagers purchased lots from a developer and either built the cottages themselves or contracted the work to local carpenters. Often the cottage began as a simple lean-to or a tent. Each year the cottager made improvements until he had a cabin and eventually a house. After the Second World War the number of cottages increased rapidly and by the 1950s dozens of cottages lined the lake. Many of the cottages were built on the eastern shore of the lake to take advantage of the prevailing winds and the magnificent sunsets visible across the lake. Local families sometimes own a cottage on the lake but most of the owners are from southern Ontario. Most of the cottages are occupied from June until August every year and then visited occasionally on holidays until Christmas. In recent years some of the cottages have been converted into year-round residences, especially on the southern end of the lake.

Local farmers worked as carpenters and caretakers for the cottagers and sold them firewood and other supplies. Before electricity came to the lake, Henry Erven delivered lake ice three times a week for use in iceboxes. Milk, meat and produce were also available from the surrounding farms. In the 1950s milk was delivered every other day by Johnson’s Dairy and two South River merchants sent out a catering wagon three days a week with supplies and food. Taxis from South River provided rides and carried messages to and from the train station.

Before 1950 the poor condition of the roads made a trip to Eagle Lake an event to remember. Traffic on Highway 11 north of Lake Simcoe always backed up on summer weekends as tourists fled Toronto for their cabins in Muskoka and Parry Sound. Until the 1930s the road to the Eagle Lake was over Bunker Hill whose steep eastern slope stalled many passenger cars. There was no bridge across the Narrows at Eagle Lake until 1915. A raft ferried pedestrians and horses waded across. A wooden bridge replaced the raft in 1915. In the 1950s the bridge was damaged when a steam-driven thrashing machine broke a support beam and fell through. The old bridge was replaced with a two-lane bridge. People going to cottages on East Bay turned south at Park’s Corners onto the old Muskoka Colonization Road. They parked their cars at the Art Edwards’ farm at the western end of the 2nd Concession Road and walked down the hill to their cottages on the lake. In the 1930s Art Edwards and Henry Erven built a road along the eastern shore of Eagle Lake to move farm machinery between their farms and around 1938 the township agreed to improve this road and extend it to connect to the Eagle Lake Road. This road is now called East Bay Road. Sometime after 1940 the road to Eagle Lake was rerouted to bypass the steep hill at Bunker Hill. In the middle 1950s the Province of Ontario opened the Mikisew Provincial Park on the west side of Eagle Lake and the Eagle Lake Road was improved and paved from Highway 11 to the park’s entrance. In the summer of 1951 Ontario Hydro extended the electrical grid to the lake. With the roads improved and electricity extended to the lake, the number of cottages increased yearly and the tourist trade became an important factor in the Township’s economy.

Part 4 – The Uplands Community 1880-1980

http://www.ragnarokr.org/index.php-title=The_Uplands_Community,_1880-1980.html

Uplands Community 1880-1980

In the “horse and buggy days” travel was often difficult and time consuming and people rarely ventured far from home. Their world centered on their neighbourhood which was often limited to the area within about three miles from their residence. Women, especially, were confined to the immediate area of their homes. Men were far more likely to travel and occasionally made long treks on foot to purchase supplies. Several pioneer families handed down stories of their grandfathers carrying bags of flour long distances from a gristmill without either a horse or a mule to lighten the burden. During the many months of winter the trails were snow-bound and, in the spring, muddy. Under these conditions, women left their neighbourhood only two or three times a year to visit friends and relatives or to attend an event such as the Agricultural Fair or the July 1st Picnic at the Eagle Lake Narrows. Travel was sufficiently difficult so that it was not uncommon for visitors to spend the night rather than risk returning to their homes after nightfall. Logging bees, barn raisings, community picnics and protracted meetings were often two-day affairs for this reason. Travelers caught on the road after nightfall did not hesitate to turn into the first driveway they came upon where they were virtually assured of being offered space either in the house if they were “respectable” people or in the barn if they were labourers or strangers. Each community had its own school and school children usually were able to walk to school in about half an hour.

Due to a shortage of gospel ministers willing to serve in frontier areas, only three churches were located in the rural part of Machar Township before about 1940. This meant that some of the congregation traveled four or five miles to attend church. However these churches did not have services every Sunday. The ministers assigned to these churches were responsible for several parishes and in some years the minister’s post was vacant. The ministers traveled great distances, often on foot, to evangelize, visit the sick and to encourage their congregations. In the absence of a church building, services were held in different homes, usually once a month. Often the missionaries were seminary students on temporary assignment.

After the Eagle Lake United Church was built in 1884 a number of families attended services there if the weather and the roads permitted. The Eagle Lake United Church was the largest of the rural churches as well as the oldest. It was located near Eagle Lake east of the Narrows. It was originally intended to be a United Church serving both the Presbyterian and the Anglicans. However, the Anglicans withdrew from the church soon after it was built and in 1888 built St. John’s Anglican Church at the northern tip of the lake. A Methodist Missionary Preacher held meetings once every third week in a house halfway between South River and Sundridge. Some years later the Methodists erected a church near Hamilton Lake. Both the Methodist Church and the United Church were abandoned as the rural population declined. The Eagle Lake United Church was abandoned in the 1950s and the building burned in the early 1960s. St John’s Anglican Church is still an active parish. In addition to these rural churches, there were churches in the village of South River including Grace Anglican and Chalmer’s United Church.

In 1900 there were 101 households and 500 inhabitants in the Village of South River and 64 households and 315 inhabitants in the rural parts of the township. The population of the village were mostly employees of the large sawmill there and about a quarter of the population lived in rented houses, some of which belonged to the sawmill. In contrast, the rural population was largely free-holding farmers and only about ten percent of the farmers leased their farms from someone else. Ninety percent of the farmers owned one or two lots and worked the land themselves. In 1900 there were ten vacant houses in the township and a few men were beginning to accumulate land purchased from neighbours who had moved to town or gone west. About one-third of the farmers had some source of income other than their farm. Most of the farmhouses were single-family dwellings and were occupied by the owner and his wife and their children. About half of the houses had four or more rooms but about 25% were one- or two-room cabins. Families with four or five children and living in a one- or two-room house resorted to extraordinary means to meet everyone’s need for privacy. Quilts or blankets were hung up for partitions and children shared beds. Everyone put on bed gowns before going to bed. After the candle had been blown out, they wiggled out of their outer garments only after they were in bed.

Not all of the township’s rural residents were farmers. A person who did not farm headed twelve of the 64 households. There were four teachers, three full-time labourers, one cheese maker, one mason and one carpenter residing in rural Machar Township. Among the lodgers were two store clerks and a man who owned a sawmill. The Census of 1901 found 148 adults and 167 children in the rural part of the Township. Of those children 32 were registered in one of the three elementary schools. The village of South River had 248 children of which 159 were enrolled in school.

The Uplands Community: The Uplands of Eagle Lake

In 1900 the township contained six named communities in addition to the village of South River (then called Machar). Each community had a post office and most had a school. Four of the communities (Eagle Lake, Stewart Bay, Midford and Uplands) bordered on Eagle Lake. The community of Mandeville lay astride the Jerusalem Road that linked the Nippising and the Muskoka Roads in the northwest corner of the township. The community in the northeast part of the township was called either Bray Lake or Hamilton Lake or both. The school was located near Hamilton Lake but the post office was located nearer Bray Lake. Some of the students from the Hamilton Lake community attended school in Granite Hill on the northern border of the Township. Each of these six communities consisted of from eight to twelve households and in 1900 the four rural schools registered from ten to twenty students each. Soon after 1900 two more schools were constructed to accommodate the growing number of school-age children.

The community of Uplands was located just east of Eagle Lake on the ridge that extends north and south across the middle of the township. The ridge wraps around a large eastern bay of the lake and the area was known as the Uplands of Eagle Lake. The Uplands community was the Township’s first commercial centre. In 1900 the community was bounded on the south by the boundary road that runs between Machar and Strong Townships, on the west by Eagle Lake, on the north by the community of Midford and on the east by the Tyerman Marsh. By 1890 almost the entire township had passed into private hands. Prior to 1890 there were about a dozen households in the Uplands community. This number included John Armstrong who made cheese and Peter Shaughnessey who operated the Uplands store. By 1900 there were about 18 households in the Uplands community but by 1920 the number of households had decreased to less than 12. In 1920 most of the community’s surviving farms were on the high ground at Bunker Hill, Edward’s Hill, around East Bay and along the Eagle Lake Road to the Narrows.

Among the first settlers to claim land in the vicinity was John and Flora Campbell. They arrived from southern Ontario soon after the Township was opened for settlement in 1876. A few years later, when Flora’s younger brother, George Bow, claimed two hundred acres near the Eagle Lake Narrows, there were already a number of families living in the area. The Muskoka Colonization Road reached the Township by 1878. A merchant named Peter Shaughnessy arrived before the road was passable and entered a claim to two lots at the southeast corner of the intersection of the colonization road and the 2nd Concession Road allowance. Two years later, in 1880, Richard Cole and his sons cut a trail following the road allowance to Lots 12 and 13, Concession 3 on the eastern side of the Tyerman Marsh. Later that summer, a group of men followed the trail to the banks of the South River where they built a cabin on Lot 6, Concession 1. Others quickly joined these men, all seeking to homestead. In 1882 a merchant, Mr. Holditch, put in a small store facing the 2nd Concession Road allowance near the west bank of the South River. The J.R.Booth Company maintained a logging camp east of the South River and this provided a market for the store and for the milk and eggs offered by the settlers. In 1884 a sawmill was built near the store and in 1885 Robert Carter opened the town’s first general store.

The next year the Grand Truck Railway reached the site. The railroad built a station for freight and passengers, giving it the name of “Machar”. After the railroad began regular passenger and freight service to southern Ontario, the village grew rapidly. A large two-story hotel and restaurant called the Queen’s Hotel was built in 1887 next to the tracks. In that same year a large steam-driven sawmill was built above the dam that had been constructed by the J.R.Booth Company. By 1900 the town had six stores, 131 homes and 147 outbuildings. In 1902 the King Edward Hotel was built across the street from the Queen’s Hotel.

The Uplands Community: Country Crossroads Store

The presence of the railroad terminal shifted the economic focus from the colonization roads to the railroad. In 1895 the 2nd Concession Road that had been cleared by Robert Cole in 1880 was improved and renamed the South River Road. The road began at the village and terminated at the Muskoka Road about five miles to the west. For a few years it was the only road linking the settled areas of Machar and Lount Townships to the Machar Railroad Station. Peter Shaughnessey had put in a store at the intersection of the Muskoka Road and the South River Road sometime before 1895. He had also been appointed the first Postmaster in the Township and had officially named the settlement “Uplands”. Shaughnessey’s sleigh or wagon made regular trips to Rosseau or Magnetawan to purchase supplies for his store. He did hauling for other people and carried the mail before the arrival of the railroad. His crossroads store prospered and he became a relatively wealthy man. He was one of the organizers of what became the Eagle Lake United Church but withdrew from the building committee when it became clear that the church would not be built at Uplands. In the Census of 1901 he listed land holdings of 1100 acres, making him the largest landowner in the Township. He did not farm this land but leased it to other, younger men. He hired a female clerk to work in his store and a teamster to manage the cartage service. He served as the Reeve of the Township from 1902 until 1905 and was instrumental in having the Upland’s School relocated next to his store in 1902. He died in 1904 at the age of 67.

The community of Uplands had two crossroads stores. Peter Shaughnessy’s store was located at the intersection of the Muskoka Road and the South River Road. A second commercial centre grew up a mile north of the Upland’s Post Office at the intersection of the Muskoka Road and the 4th Concession Road. The 4th Concession Road (better known as the Eagle Lake Road) led to the ferry crossing at the Narrows of Eagle Lake. Practically all of the traffic from the northern and western parts of the township passed through this intersection. John Parks settled on land south of the 4th Concession Road and on either side of the Muskoka Road in 1881. In 1887 he had met the requirements of the “Free Grant and Homestead Act” and received title to the land. In 1890 he sold two small parcels to a widowed relative for twenty dollars. The widow, Jessie Parks, built a store on the two-acre parcel at the southeast corner of the crossroads and a house on a twenty-acre parcel across the road. Both buildings have long since disappeared but the stone foundation of the store building remains. This intersection was long known as Park’s Corner. On the north side of the concession road, Mrs. Little opened her farmhouse to travelers and this became known as Mrs. Little’s Boarding House. Jessie Parks ran the store at Park’s Corner during the 1880s and 1890s. In 1896 John Parks sold his share of the property to a teacher at the Uplands School and moved to Huntsville. The store may have been closed by that time.

The farms surrounding Park’s Corner were all settled in the 1870s and 1880s and have been farmed continuously since. The area is now known as Bunker Hill and remains the home of locally prominent families. Bunker Hill is on the eastern slope of the ridge that bisects the Township and the farms overlook the valley at Robertson’s Flats. The township road climbed straight up the eastern slope of the ridge and, until about 1950, the road was so steep it was impossible for some motorized vehicles to climb it. In the summer some automobiles had to climb the hill in reverse gear and in winter the cars could not get up the hill at all. When the Province of Ontario opened the Mikisew Provincial Park on Eagle Lake in the 1950s the road was rerouted to avoid this steep part.

The high land surrounding Park’s Corner proved to be the best farmland in the Uplands community. The ridge at this point sloped slightly to the south and east and was broad enough to contain pockets of deep, if sandy, soil. The settlers found that fruit trees and field crops were less likely to be damaged by early frosts on the hilltops than on the flats. Farmers on the hilltops planted orchards of apples, plums and butternuts and sometimes hops and grapes. In the winter the snow pack was not as deep and, in the spring, it melted sooner. Gardens could be planted earlier and continued to produce longer than those in the valleys where the frost gathered on cold autumn nights. In the summer the prevailing westerly winds swept the black flies and the mosquitoes away and the animals and residents on the hilltop farms escaped the annoying clouds of insects that plagued the low-lying farms.

The Uplands Community: The population declines

Between one-quarter and one-half of the pioneers who settled Machar Township before 1900 moved either west to the Prairies or returned to southern Ontario, often in their old age. Those who stayed died on their farms or in South River or Sundridge. The children who grew up on the farms left the area in overwhelming numbers. As a result, between 1900 and 1930, the number of rural farm households in the township decreased by 40%. Settlers continued to move into the township after 1900 (although in much smaller numbers) but their children too left the area. About 75% of the children of the settlers left the area once they were grown. This trend has continued and between 1930 and 1960 the number of households in the rural part of the township decreased by a further 30%.

The land rush that populated Machar Township proved to be a speculative bubble. The Provincial Government opened the land for settlement in response to intense land pressure in the settled parts of Ontario. However, soil science was in its infancy and the agricultural capacity of soil was judged solely by the presence or absence of large trees. Neither the authorities nor the settlers could have known that the region had little agricultural potential. In addition, the land was opened for settlement in 1875 during the depression caused by the Panic of 1873. The resulting depression lasted from 1873 to 1879 and caused many business failures, the closing of many industrial plants and the suspension of railroad construction. Hundreds of industrial workers lost their jobs and some of them decided to return to farming while they waited out the depression. They waited for many years for a return to prosperity. It was not until 1887, fourteen years later, that Canada fully recovered from the business slowdown caused by the end of the Civil War in the US.

In 1887 Canada experienced its first period of real prosperity since Confederation. The long period of price depression came to an end largely because of the high price of wheat. In response to the high price of wheat large numbers of immigrants arrived in Canada, mostly headed for the West to homestead on the Prairies. Between 1899 and 1916 the population of Canada increased over 34%. The village at South River literally boomed into existence with the arrival of the railroad in 1886. The railroad made it practicable to transport timber products to markets in southern Ontario and the prosperity of the township depended completely upon the sawmills and the railroad. But this prosperity had little effect on rural Machar Township. Despite the hopes of many farmers, the arrival of the railroad did not spark another land rush. Those who had hoped to sell their farms at a large profit were disappointed. The poor soil and the harsh climate prevented area farmers from competing successfully with farmers elsewhere. Hay, oats and root crops were more profitable in the clay belt northwest of Lake Timiskaming. Vegetables and fruit were more profitable in southern Ontario and grain on the Prairies. For 50 years the many sawmills in the area provided seasonal employment and a ready market for saw logs but, in the long run, competition from sawmills in British Columbia and the steady decline in the quality and quantity of the area’s saw logs doomed these mills. The children of the pioneers had little choice except to leave the farms and find work in either South River or in southern Ontario.

In 1881 Robert McDonald (nicknamed Pool) settled on Lots 19 and 20, Concession 3, at the northeast corner of the Muskoka Road and the 2nd Concession Road. His house was east of and downhill from Peter Shaughnessey’s store and home on Lot 20, Concession 2. Across the Muskoka Road was the farm of James Jones at Edward’s Hill. The house McDonald built was slightly uphill from a small stream that runs down the hillside from a large bog on the high ground to the west. The house overlooked a small valley on the shoulder of the ridge. By 1901 the neighbouring farmer to the east abandoned his cabin and sold his land to Alphonse Little, who lived with his parents at Park’s Corner. This left the McDonald farm as the only working farm between the Uplands Post Office and Cole’s Hill. After the death of McDonald, Stuart MacAlfie farmed the land followed in turn by Arthur Bow. The sandy soil was suitable for potatoes but by the 1930s the fields were abandoned and were being used as pasture and for hay. Occasionally a field was planted in potatoes. This kept the fields clear of trees and underbrush. After Art Bow stopped cutting hay from the fields, the forest trees gradually invaded the fields and by 1970 Pool McDonald’s farm was largely overgrown and had returned to forest. The house had completely disappeared except for the presence of a few old and overgrown yard plants.

In the 1920s Art Edwards came to the township to work as a butcher in the logging camps. He married the daughter of William Jones who had inherited the James Jones farm on Lots 21 and 22, Concession 3. This farm was at the crest of the ridge and overlooked and abutted Eagle Lake. Art Edwards purchased the farm from his father-in-law and raised his family there. In addition to the usual farming operation he raised sheep and sold milk. The teacher at the Uplands School usually boarded with the Edwards family and the school picnic was held on the Edwards property along East Bay. Art and his neighbour to the north, Henry Ervin, encouraged and sold meat, milk and ice to the tourists that were beginning to build cabins on the East Bay. They were instrumental in building the road that runs along the shore of East Bay. In 1936 Art marked off his lakefront property into a number of small lots and began to sell building lots to cottagers. When he and his wife Violet died, the farm was abandoned. The farmhouse has been moved off its foundations but remains near the original site at the highest point on the ridge and overlooking the lake.

The Uplands Community: The Uplands community disappears

By the 1930s all but three of the farms along the 2nd Concession Road west of Cole’s Hill had been either sold to Standard Chemical or were no longer regularly cultivated. Standard Chemical purchased many of the lots along the 2nd Concession Road west of Cole’s Hill during the 1920s at low prices. The company used cordwood as feedstock in its chemical plant. It purchased cordwood from landowners and also employed contractors to cut the wood on its own property. In the early 1930s one of these contractors built a camp for his workers across the Muskoka Road and a little downhill from the Uplands School. This was called the Walsh Bush Camp. The men employed to do the work were immigrants from Finland. They had originally landed in southern Ontario but came north seeking employment. At least twelve families of Fins came to live in Machar Township and several families remain in the area. The Walsh camp had small individual cabins for each family, a root cellar and a communal kitchen. In their spare time the men made and sold skies and sleighs. Some of these families later purchased farms in the area and found work in sawmills. The United Church minister who was pastor of Chalmer’s United Church and the Eagle Lake Church in the 1930s and 1940s reportedly learned the Finnish language from these immigrants.

Standard Chemical maintained the 2nd Concession Road (the old South River Road) as a winter road long after it had ceased to be useable in the summer. It was used to haul timber to the chemical plant in South River. The last inhabitants along the road lived on Lot 18, Conc. 2. They left the area in the 1940s. By 1970 their cabin’s roof had fallen in. After the farm on Edward’s Hill was abandoned the road in that direction also grew up in trees and a beaver pond covered the road to the Edward’s farm in the 1970s. The farms and the cheese factory along the Boundary Road had all been abandoned by 1930 except for the farm on Lots 15 and 16, Concession 1. Harvey Pinkerton Sr. purchased that farm from William J. Snow in 1925. From 1932 until 1952 he sold milk door to door from his dairy there. In 1952 Harvey Pinkerton sold the farm and moved briefly to Bunker Hill. The farm on the Boundary Road continues to be occupied as a residence.

The Uplands store closed sometime after the death of Peter Shaughnessey. By 1970 only traces of the foundation of the house and store remained. The Uplands School was closed in the 1930s and the children reassigned to the Hawthorne School some three miles north. Violet Edwards drove the children to the Hawthorne School in a car when the roads were passable. In the winter the children were transported by bobsleigh and in the spring they rode the family’s workhorses. Sometimes seven children rode the two horses to and from school. The school board sold the Uplands School as a residence to William McVittie. For many years, after the Edward’s farm was abandoned, the old stone school house converted to a cottage was the only building on the side road between the 4th Concession Road and the Boundary Road. The owner painted his name on a large rock at the corner of the old Muskoka Road and the Eagle Lake Road and the road was called McVittie’s Road until about 1970. This section of the Muskoka Road was kept open in the summer as a short cut to Sundridge but in the winter it is not ploughed. In the late 1960s a German couple purchased Lot 21, Concession 2, and built a small cottage in the woods across from the old school. In 1970 a group of hippies from Toronto purchased Lot 19, Concession 2 and over the next ten years built a number of homes and cottages in the valley at the foot of the hill. In the 1970s Larry and Barbara O’Rourke built a retirement home on the site of Peter Shaughnessey’s home. Jack and Jean Ivans later purchased this house. In the late 1970s Carl and Barb Hann built a house on Lot 20, Concession 3 and in the 1980s Paul and Carol Fogerty built a home on Lot 21, Concession 3 on the west side of the Muskoka Road. The hippies cleared some of their land and experimented with various crops. They also installed a workshop and a sugar bush. In some ways and for a short time, the Uplands community came alive again.